Why Is Validation Hard For Founders?

“Most entrepreneurship is differentiating between ‘good-sounding dumb ideas’ and ‘dumb-sounding good ideas’ – Aaron Gotwalt

One of the hardest questions that a founder carries around with them is “Is this going to work?”.

It comes from a good place, but it’s not a good question.

That’s because it suggests a binary answer – yes or no.

It will work, or it won’t work.

But in the vast majority of situations, a more accurate answer would begin with the words “Yes, if…”:

Yes if we can find our minimum viable audience

Yes if we can secure the right supplier arrangements

Yes if we’re sufficiently better/different to our competitors

Yes if we have the right team and a healthy culture

Yes if we can make enough of a margin

Yes if we can stay creative and avoid getting stuck

Again, these aren’t static scenarios.

Audiences churn and need to be replenished.

Competitors don’t stay still, they adapt and innovate as well.

Your team will change, and stressful times will test your culture.

Margins need to be defended, both against creeping costs and price competition.

So a founder now has to think several moves ahead.

Like in a game of chess or Connect Four, you’re not just thinking about your move, you’re also anticipating responses and a changing landscape.

And while you can try to influence your opponent, ultimately their actions aren’t yours to control.

It also means that a founder’s confidence won’t be static either – they might feel great about their prospects, but a new piece of information or unpleasant surprise suddenly changes their outlook, and it could change back equally fast.

A Better Question

Instead of “Is this going to work?”, a better question is “How might this work?”.

It’s a small change but “How might…” invites possibilities, alternatives and scenarios.

One of the best and worst parts of business is that there’s not one singular way of doing things that can succeed.

Rory Sutherland says “The opposite of a good idea can also be a good idea”.

So not only are there a lot of options, but a good and bad option can look nearly identical, and two good options can look alarmingly different.

“How might this work?” acknowledges that there are a range of scenarios on the cards, involving pivots, luck and unexpected plot twists.

You could:

Target a different customer

Design a different solution

Position yourself differently

Created a different brand

Operate in a different part of the value chain

Create different revenue streams

It could be one or several of these in combination, lots of scenarios to consider.

That’s what makes “How might” such a good question – because we realise how arrogant it would be to rule out all of the possibilities.

Grappling With Multiple Futures

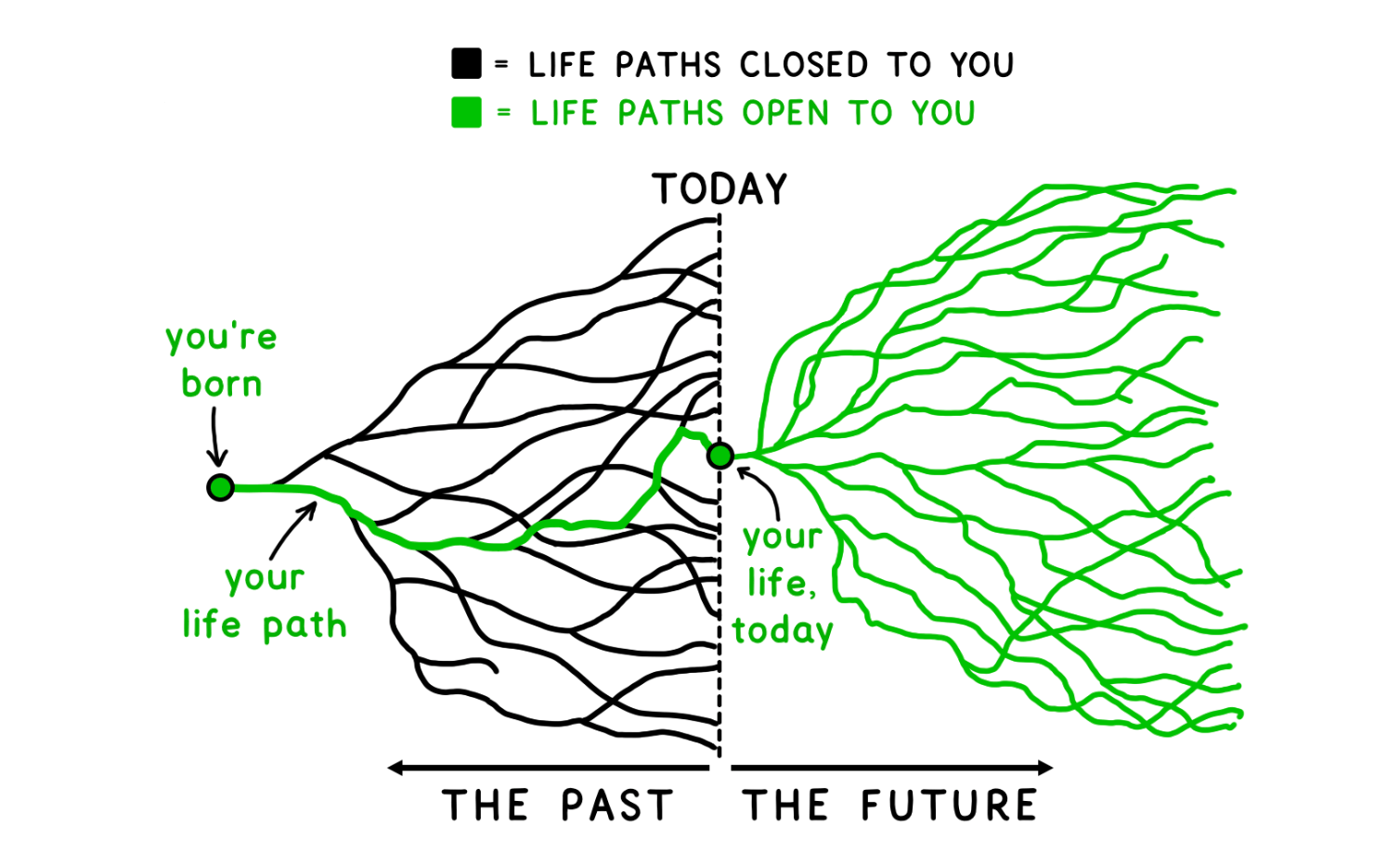

Tim Urban created a wonderful diagram:

Tim Urban, waitbutwhy.com

It’s a lot to take in.

We have to acknowledge the enormous number of scenarios, choices and changes that have led us to where we are today – all of which is clear in hindsight.

Then there’s the future, full of possibilities and future forks in the road, most of which we can’t currently see.

There are many different possibilities for the future, and so while entrepreneurs are encouraged to describe vivid visions, they’re wishing, not predicting.

One perspective that helped me understand the balance between visions and tactics came from Seth Godin:

"Persistence isn't using the same tactics over and over. That's just annoying. Persistence is having the same goal over and over".

By all means, stick to your principles, but don’t latch on to specific tactics or details too tightly.

Sitting With Uncertainty

Founders have to get comfortable with uncertainty – something I found really difficult in the early days of The Difference Incubator.

One of the best questions for speeding up progress is to ask “Which part of this work is the hard part?”.

Most projects have a lot of basic, unremarkable work to be done, and a few creative tasks that are difficult or are rarely done well.

Some elements can be done to an 8/10 standard and be fine, and some parts need to be crafted with care and generosity in order for the project to work.

In some cases, the hard part is at the start – the act of creating something new, or introducing a new concept to an unfamiliar audience.

Other times the hard part is continuing to do brilliant work without dropping your standard or cutting corners – taking the work unreasonably seriously.

It’s different for every project, but you probably know which part is the hard part in your specific situation.

The next great question is “Can we do the hard part first?”

The straightforward work is comfortable – we can forecast it accurately, do it on autopilot, or outsource it and feel confident that the work will be done to our satisfaction.

The hard part is the unknown – is the design good enough?

Will the work be appreciated?

Is the plan feasible?

Will people pay a fair price?

Can we build demand?

Finally, rather than making a massive declaration or commitment, we ask “can we start with a cheap bet?”.

This might be a paid ad, some pretotyping, mock ups, specialist input, or a few pieces of content designed to test our assumptions and generate honest reactions.

You’re allowed to spend some money, it can speed up the process if you’re intentional, but spending lots of money can’t spare you from the discomfort of trying something that might not work.

Red And Green Flags

Because we get to work with a lot of founders and teams, we’ve developed some indicators that show how realistic a founder is being.

Some of the Red Flags that usually precede trouble include:

Outsourcing the learning to their team or a consultant

Acting like the work is easy

Acting like success is inevitable

Assuming that obtaining outside investment will fix any issues

These are unhelpful because the founder isn’t listening to the market, nor are they making subtle and frequent adjustments to their ideas based on feedback and new possibilities.

Green Flags that stand out include:

A founder seeing scenarios and different possibilities

Acknowledging and valuing the hard parts of the work

Making small bets and running small tests before making sweeping decisions

Beginning to plant seeds long before they need a harvest

Putting in effort to give their work a great chance of succeeding, but not pretending to ignore any failures

These are good signs because they show a founder who is paying attention to the market, without being spooked or brash.

Validation is a constant part of entrepreneurship – it isn’t ever finished.

Failures aren’t permanent, neither are successes.

The job of a founder is to be like a pilot – paying close attention to what’s in front of them, how they’re tracking towards their destination, and making frequent small changes to stay on course.

Some parts of the work can be done on autopilot, but it takes an expert with decades of experience to know how to avoid storms and make big calls.

Keep an open mind, ask how you might succeed, and try to do the hard parts first.

And remember – things are never as good and never as bad as you think they are.