Testing Your Menu With Customers

"I'm impressed with people who can create new spaces with the right words."

- Andy Warhol

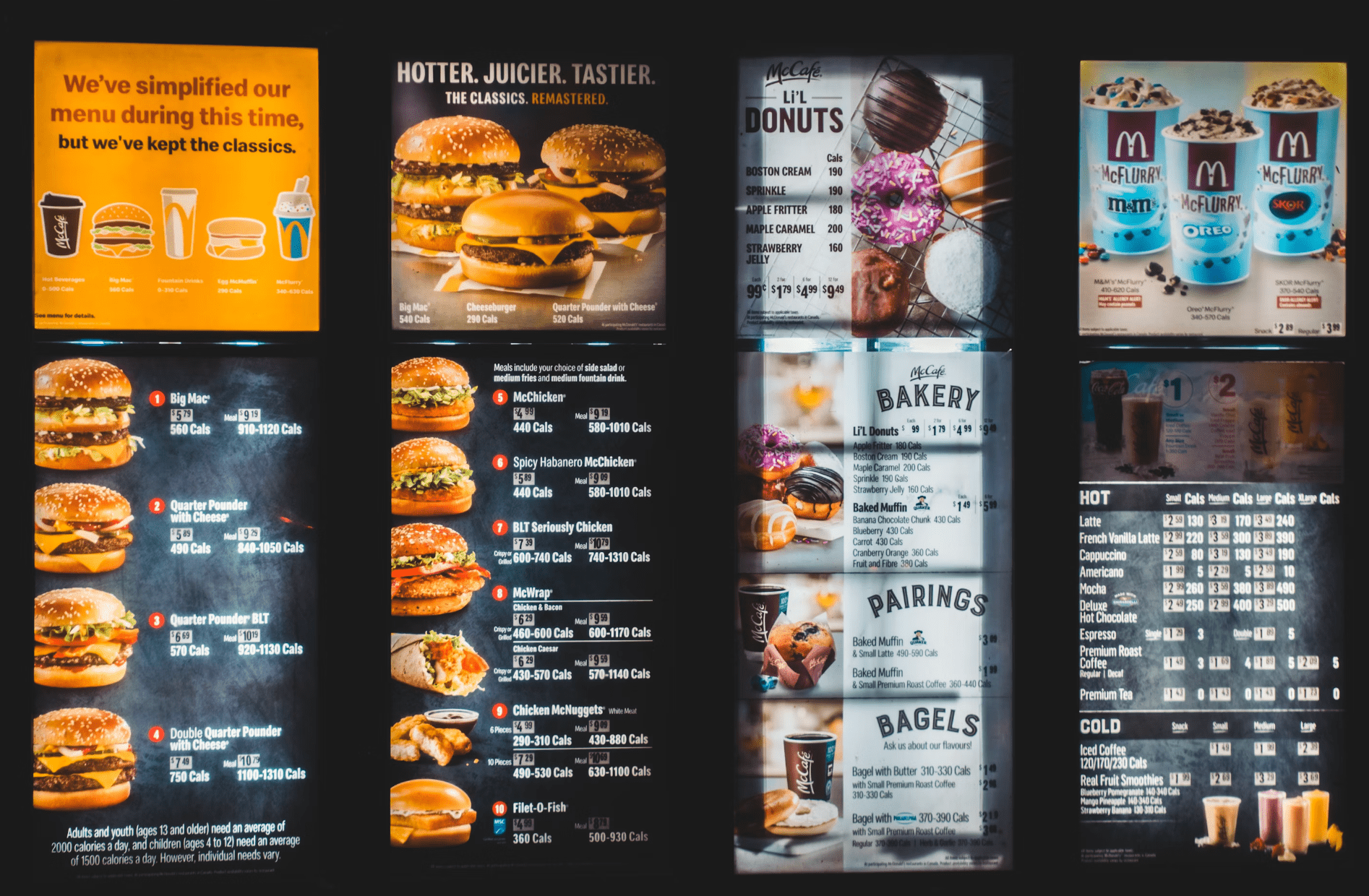

We’ve previously discussed how an entrepreneur can think about what’s on their menu – the collection of products, services and offers their startup might sell.

This is helpful for identifying opportunities to create a range of offers, not following the conventions of your industry.

Now we get to show these menus to customers, figuratively and literally, to understand their levels of interest.

We are at the crossover between customer-problem fit and product-solution fit.

We’re clarifying and confirming who our customers are and what they care about – our guesses were probably close, but there’s usually a few surprises.

We’re also ideating on various ways of solving their problems or creating delight – offers that might prompt customers to say “shut up and take my money”.

There’s overlap between these stages, we don’t need to be “finished”, as new insights can lead to brilliant opportunities in the future.

Four Laminated Pages

When we first started The Difference Incubator, we had a half-built office, two desks, two laptops and four laminated diagrams.

These four pages described our methodology, the different ways in which we could help people, and some of the tools we typically used.

I’d meet potential customers for coffee, listen to their stories, ask them questions and talk about my four laminated pages.

They might be polite and part ways, they might ask questions of us, and some of them asked to find out more about our different services.

If you have a few of these chats each day, you get a decent sense of what the market finds relevant.

I knew I was just a person with laminated diagrams, but to the world we were a business with interesting offers, and that was enough to get started.

Better yet, the act of showing people that menu and hearing their questions highlighted tweaks that might better serve the market, as well as entirely new offerings that might be relevant.

Laminating the pages made them look legitimate, but it also gave them a sense of permanence that they probably hadn’t earned.

The truth was, we were changing our model by the month, but customers don’t want to know that.

Why Test With A Menu?

This is the most foundational form of prototyping: testing and toying with concepts and names - the very idea of something that could serve and delight a customer.

We are speaking ideas into existence; there’s no cost, except for our time and the courage to show it to the market.

Customers act differently when reading than when they’re in a conversation.

Unlike an enquiry or negotiation, most people are too busy taking in your brand, your offers and your price points to put on a performance.

You can tell if they’re flicking through out of courtesy, or if they’re genuinely reading.

You can watch how quickly they turn pages, skim over certain categories, fly through your website, and see where they drop anchor.

What makes them stop scrolling?

Where do they ask questions?

What links do they click?

What do they mention in an email?

A menu item is not a promise, it’s an introduction.

We don’t have to 100% know how to make it a reality, and a customer isn’t 100% committing to it.

This is flirting, putting our best foot forward, trying to seem effortlessly charming, all the while looking for mutual interest and a sense of chemistry.

Is the customer open and curious?

What registers on their radar?

What catches their eye?

What Might Go On Each Page?

Your menu might be a single page, or a few different styles of offer, potentially at different price points or for different customer segments.

Have a look at each of these and see what resonates - feel free to borrow some of each, or narrow your focus as you test your approach

Free samples – offers that don’t cost anything for customers, because they are designed to make your brand know, liked and trusted.

Content that hooks customers in

Lead magnets that give the customer something valuable, albeit limited

Free trials that don’t require credit card details

Events open to the public

Appetizers - easy and early introductions to your work, with the hope/expectation that customers will buying something more substantial later.

Low price starters, which are useful but invite further purchases

Freemium offers, where you use a paywall to offer limited perks or features

“Razor and blade” models where a customer needs to buy refills or replacement parts in the future

A La Carte – customers choose products and services off the shelf, big or small, and each purchase could be the last time they shop with you.

Pay for what you use offers like a low-cost airline

Readymade products sold through a retailer/distributor

Services by the hour, with no ongoing commitment

Standalone workshops and events

Banquet – a comprehensive and sometimes generous package deal; there’s a sense of it being unlimited and inclusive, and often they’re not cheap.

Subscriptions without consumption limits

Seats on a platform, going up as you add more team members

Retainers for ongoing professional services

Custom Orders -tailored, expensive, and convenient, these appeal to a limited market with specific needs and deep pockets

Co-created projects

White labeling

Luxury offers

Innovation can come from selling the same underlying benefit as competitors in a new way, to a new audience, or using a different payment mechanism.

Coffee can come from a can, a bag of beans, a pod machine, a chain brand café, a specialty roaster, or rare beans that have been “pre-digested” by Indonesian Civet Cats. You pay totally different prices, and these have wildly different flavour profiles, but the market is so broad that there’s room for many different models to co-exist.

iTunes disrupted album sales by letting customers pay for individual tracks and offering 30-second song previews. Spotify, in turn, disrupted iTunes by offering comprehensive streaming catalogues, with an intentionally horrible free version designed to push people to paid memberships.

Canva and Adobe both offer graphic design tools, to different sorts of customers. Adobe switched from selling software to selling subscriptions, while Canva is an online platform with Freemium features that democratised and simplified previously complex design tools.

Airbnb offered a compelling alternative to hotels, but their offers have gradually become less and less customer friendly. Now with comparison sites like Expedia and Trivago, hotels are becoming more appealing, with no additional cleaning fees or expected labour on the part of the customer.

Good Questions For Determining Your Strategy

You cannot be all things to all people, so you’ll need to determine some parameters around where you’ll play, how you’ll succeed, and what tradeoffs you can live with.

Rather than answers, here are some good questions to get you thinking:

Does one size fit all? How much variance and customisation truly serves the customer and their needs?

Is there value in offering a good, better and best option? Does it need to be more sophisticated than that?

Can the customer pay more get more, and/or pay less get less?

Who’s it not for? Who are we content with not wanting/being able to shop with us?

Tim Ferriss said “My ideas are free and my time is expensive” – how much does this resonate with us?

Where do we put our paywall? At the start? Do we let customers use certain features, or the full experience for a certain amount of time?

How much does a customer WANT to spend? What’s their budget and how did they arrive at that number? What will they do with any money they can save?

Is this best handled as a relationship or a one-time decision? What would our customers prefer?

Am I talking to the decision maker, the end user, or both? What’s at the top of each of their priority lists?

How much responsibility are we taking for the customer’s success? Who owns the risk? Can we offer any forms of guarantee?

What would the customer wish for? E.g. getting large tattoos under general anaesthetic - something that didn’t previously exist but would delight a market who would have been put off by hours of pain in the chair

How does the customer measure value, or how they measure cost? i.e. per unit, per month, cost per use, price of the next best alternative, the total lifetime cost?

How much education does the customer need?

How much personal attention does the customer need?

These questions should give you a sense of what is helpful to offer on a menu, and crucially, what might be unhelpful to offer on a menu.

While it’s good to test new concepts, “courtesy offers” serve no one.

If a customer shows interest and you’re upset or annoyed, don’t make it an option.

Measuring Customer Responses

The test of a menu is attention and inquiry.

What catches their eye, what surprises them, what intrigues them, what resonates?

Dave Trott always says that 4% of advertising is remembered positively, 7% is remembered negatively, and 89% isn’t remembered at all.

That’s what we’re up against – glazed eyes and distracted minds.

We’re looking for menu items that hit a nerve and show us something about our customers, their budgets and their dealbreakers.

It’s worth recording the “Frequently Asked Questions”, both because it helps with future sales content, but also because a lack of questions is an early clue to a lack of genuine interest.

Some offers benefit from a mock up, a case study or an explanation, and some are self-explanatory.

Would a visual help to capture attention and demonstrate your strengths?

You can also do this through testimonials and customer stories – showing how you help people in case it’s not obvious.

If you’re unsure, try two versions and measure the response rates.

You get different types of insights from digital and observational metrics.

Clicks and impressions are easy to track but hard to deduce - who saw them, in what context?

What were they looking for on your page/site?

Where did they go immediately afterwards?

Body language and conversations are richer, but more limited.

You can separate what someone says from what they might mean, reading into tone, answering their questions along the way.

But there’s the sampling bias from only talking to people who want to talk to you, which has mixed benefits.

In the case of The Difference Incubator, I was only talking to extroverts who live within range of the CBD.

That was the basis of our initial market, but later on our best clients and projects were with people who would never have met me in that café.

Interpreting Customer Responses

Keep in mind that not all attention and opinions are equally valuable,

We want to watch for false positives (compliments from people who won’t buy from you) and false negatives (skepticism/resistance from people who won’t buy from you.

What matters is the opinion of customers who vote with their feet and vote with their wallet – do they back up their words with actions or cash?

I once worked with a colleague who would put down his pen when he’d given up on a conversation – usually 10-15 minutes before the conversation ended.

Once the pen went down, his mind was made up, and any words after that point were out of courtesy to the other person.

You can look for this moment with your customers – when are they speaking from self-interest, and when are they just being polite?

We’re looking for commitment and advancement; evidence of a customer taking some sort of next step, or giving up something of value to them.

It’s worth setting a target for level of interest to see which options are worth developing further, e.g. talking to 20 potential customers, and wanting to see at least 5 of them take a next step or make some sort of pre-order.

If you feel someone is on the verge of a decision, you can try to enquire about different sorts of remedy or add pressure to speed up the process.

This might include a discount, an offer to customise something, or adding a tight timeframe to their choices.

It helps to separate out sales objections (“I can’t proceed unless it has x, y and z”) from complaints (people who wish it was cheaper or came without any sort of compromise).

Discounts can be persuasive but also attract the wrong clientele.

The aim is to ensure customers think you’re worth a high price, but then take advantage of a reduction that saves them some cash.

If a discount brings in customers who don’t see your true value, or worse, it puts off customers who think you’re suspiciously cheap, then the discount does you a disservice.

The point of the menu exercise is it forces you to be creative and proactive.

You have to create offers that might delight your customers, but are allowed to be ignored. There’s so little cost and so little risk - the only obligation comes if you accept payment or make promises.

Make a menu that you’re only slightly embarrassed about, show it to customers in different settings, and see what responses you get.

This is like the first domino in a chain of events that might seem out of your grasp at the moment.

We don’t know what the test will prove, and we don’t need to – we need to make creative offers and pay attention to what the market is trying to show us.