Principles For Impact And Measurement

Measuring your social impact is a notoriously tricky task.

While most people would agree that measurement is essential, it’s often done in a way that is either quaint, boring, or downright deceptive.

Not many people know what to measure, nor how to read their measurements, and fewer still know how to convey those measurements into meaningful stories for decision makers.

Bill Bernbach famously said “Principles endure, formulas don’t.”

Rather than writing about specific tools and metrics that are guaranteed to become obsolete, it seems better to cover the fundamental principles behind social measurement.

These are designed to be optimistic and realistic, and to be adapted for your specific scenario.

Principle 1: Good intentions aren’t enough

For those working in the field of positive social change, you’ll know that there are stakes and urgency to our work.

If we are doing work that has a chance at making a positive difference, then it’s likely possible that we could potentially make a negative difference too – through poor design, wasted resources, bringing discredit to the field, burning people who’ve trusted you, or perpetuating unhelpful myths.

In some cases, there might be funds and an opportunity with one shot at a solution – spend it on the wrong thing, and there might not be enough resources for a second attempt.

In some cases, like when working with smallholder farmers, the stakes are even higher.

Crop failure for subsistence farmers can be diabolical.

Or in cases like public health crises, your choices can have severe ramifications.

As they say “We don’t have the right to be wrong”.

Good measurement helps us identify and remedy the unintended consequences of our work.

It helps us understand if we’re doing what we set out to do, and see if we’re unwittingly making the situation worse.

This is sometimes called “The Cobra Effect”, named after the bounty on snakes in India.

The British government offered cash for dead cobras, but this led to locals breeding more snakes to earn more money.

When this was discovered and discontinued, people let their snakes go free, and the snake infestation was worse than ever before.

Impact projects need to be taken seriously.

There should be accountability.

There should be scrutiny.

There should be an expectation of a proper process.

Principle 2: People play differently when they’re keeping score

If there’s going to be accountability, we’ll need a way of tracking what we’ve done.

That requires some form of scoreboard – indicators that show us where we are, how far we’ve come, and how far we still have to go.

These indicators are here to support our vision, but also prevent distraction and complacency from seeping in.

You might have seen people get antsy when they realise they might not hit their daily step goal, or that their social media post has very few interactions.

When we have an indicator, we naturally want to find ways of improving it.

That’s not always a good thing.

Simon Caulkin said ““What gets measured gets managed — even when it’s pointless to measure and manage it, and even if it harms the purpose of the organisation to do so”.

e.g. measuring ad impressions rather than ad revenue, measuring your number of beneficiaries but not how much you’ve helped them, etc.

So while having a scoreboard is helpful for accountability, we need to be very careful in what we choose to measure.

Principle 3: You need an opinion on behaviour change and systems change

Behaviour change and systems change are the micro and macro view of your work.

Behaviour change describes what you’d like one person to do differently, such as something they start doing, stop doing, or substitute for a new alternative.

e.g. not smoking indoors, calling out racist conversations, using reusable shopping bags.

Systems change describes what you’d like everyone to do differently, such as by changing the law, changing people’s beliefs or guiding them into new habits.

e.g. banning smoking indoors, stricter workplace/online discrimination policies, supermarkets no longer carrying single use shopping bags.

Both of these are important, because a lot of systems change starts with more and more people adopting behaviour change.

If you can’t describe why someone would be incentivised or nudged to change their behaviour, then it’s hard to see how these broader changes will magically happen.

Principle 4: You are designing a “Recipe For Change”

If you’re going to created sustained positive change, you’re going to be designing something resembling a recipe.

This describes the ingredients you use, the activities or steps that you go through, the outputs that you create, and the happy end result where you and the people you like get to enjoy your cooking.

With a well-designed recipe, anyone should be able to follow the steps and get a similar result.

In our case, this is your impact model – if you take a set of inputs (funding, team, technology), then perform a set of tasks (methodology, labour, knowledge transfer, community building), you can reliably expect to create a set of outputs (participants, beneficiaries, reduced pollution), which in turn creates a series of medium and long term benefits (higher incomes, improved confidence, higher employment, clearer waterways, reduced inequality, more diverse cultural representation).

Your recipe might look quite different from your peers, and that’s fine, so long as we understand how it works, what it achieves, and when/why it might be the right recipe for a certain situation.

e.g. you might demonstrate that while your program is not “world leading” in creating famous case studies, it is the best fit for a remote community, or a limited budget, or is the most culturally appropriate.

Your recipe will likely evolve over time, and you’ll find ways of adapting it to suit different scenarios.

Not only is your recipe a helpful way of thinking about the design of your work, it also helps you describe your “Logic Model”, which contributes to your overall “Theory of Change”.

Principle 5: When most people talk about impact measurement, they’re actually talking about outcomes measurement.

It’s good to measure the results and consequences of your work, but the terms “impact” and “outcomes” can get muddled.

Impact measurement is usually set over a longer timeframe, involving complex and expensive longitudinal studies, and can sometimes produce vague or surprising results.

Outcomes measurement often involves checking that you ended up with your desired result, measured in the short/medium term, and with metrics that are more easily attributable to your specific intervention.

For example, universities like to conduct surveys of their recent graduates, to measure how many of them are:

1) Employed

2) Employed in their chosen field, and

3) Happily employed in their chosen field

These are good because they let the university demonstrate that they are a pipeline into certain industries, and boost your chances of finding meaningful/desirable work.

Universities also like bringing in alumni as guest speakers, to talk about the work they’ve done after their studies.

These events can be engaging and inspiring, but as you listed to the alumni, it becomes harder and harder to pinpoint specific parts of their degree that led to their success.

There are probably 10-20 factors that led to where you are in your career at the moment, and tertiary education might have played a large, small or even negative role in your journey.

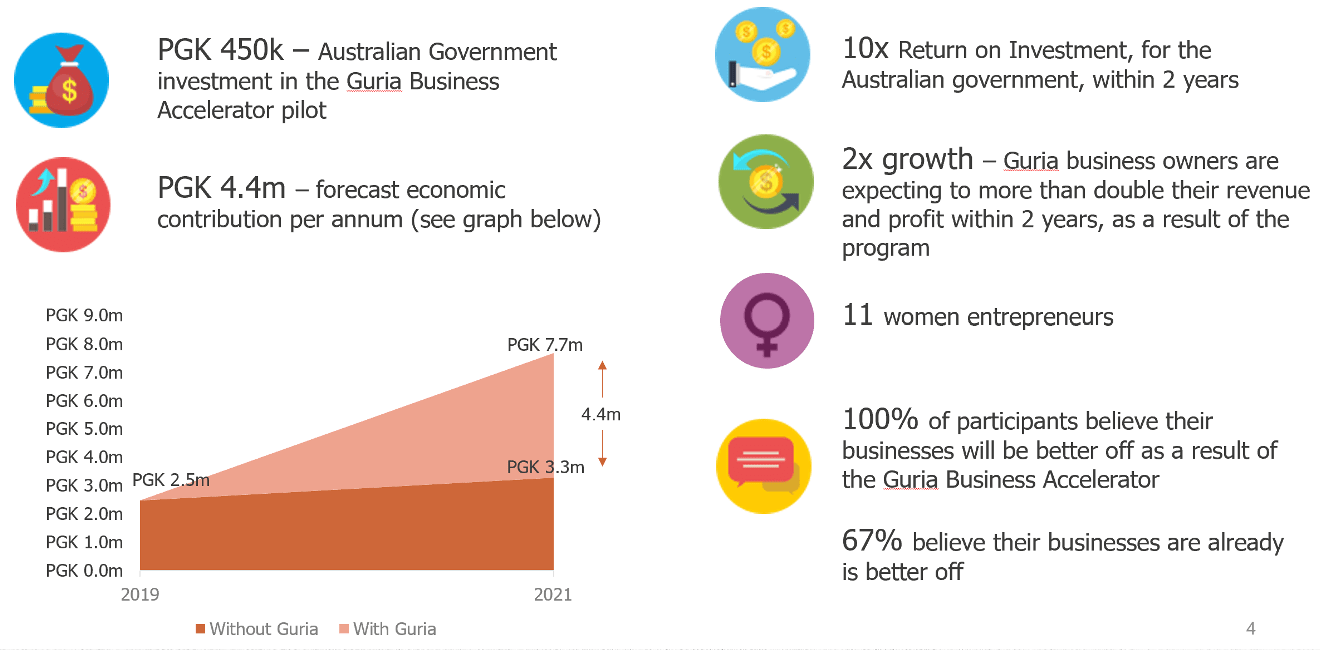

Image: The Difference Incubator

As another example, at The Difference Incubator, we take a lot of measurements at the start, mid-point and end of our programs, plus follow-ups 12-18 months after completion.

We are looking at a few outcomes in particular:

· Improved skills

· Improved confidence

· Feeling a part of a community of practice

· Clarity over their next steps

· Whether or not they’d recommend the program

· If they pivot: do they continue their good work

· If they persevere: growth in revenue, profit and social outcomes

These are what we aim for when designing accelerators, and we constantly adjust the format and content to get the best chance of reaching these outcomes.

A few themes stand out:

· Improvement is more important than brilliance, going from a 3/10 to a 7/10 in a particular skill is a great leap, whereas someone who started at 9/10 and finished 9/10 hasn’t had their expected transformation.

· Confidence is valuable alongside technical skills, some people’s self-assessed skill ratings decrease over time, as they start to see how far they have to go, but will have become more confident in their improvements.

· If you’re part of a community and feel clear on what’s happening next, you can generally get through most business problems. The reverse is not always true.

· Sometimes a pivot is the best outcome, so we want measures that help us recognise and celebrate the decision to take a few steps backwards (so long as they’re putting in good work).

· Growth in revenue and growth in profit are a good pair, because revenue growth alone can be misleading.

We’ve seen some phenomenal impacts from participants too, such as:

· Several participants joining our team as coaches

· Entrepreneurs running for local office in an election

· Huge personal transformation, in work and at home

While we celebrate these, it would be a stretch to attribute them to our accelerator, and would never expect them to occur with all future cohorts.

They are heart-warming and encouraging for our team, but they are not integral to our “recipe”.

Principle 6: Be wary of taking credit for something for which you wouldn’t accept blame.

Lots of advertising is based on the idea that “if you add/do this one thing, you’ll feel this much better”.

e.g. this new car will make you more adventurous, this shampoo will make you desirable, this ab exerciser will give you a six-pack.

It’s not that they can’t work, but rather that these things might be part of a series of changes that achieve the desired result.

The myth implied by the advertiser is these things alone will give you the desired result, and that often leads to buyer’s remorse.

When we’re measuring results and telling stories, we get to decide how much of these changes we feel should be attributed to our work.

Attribution is double-edged – if we’re going to take credit for something in the good times, we might also be held accountable in the bad times.

What are you happy to accept questions about if it doesn’t happen?

This helps you separate things that are a promise, and things that are a bonus.

You might be happy to make promises around activities and outputs, which you can heavily influence with your work.

But ultimately, you can’t force behaviour change, only create the conditions for it.

As they say, “a mind that’s changed against its will, is of the same opinion still”.

You can guarantee an effort, but not popularity.

If the thought of accountability on a certain measurement feels unfair, then it might be time to change what you’d like to attribute to your recipe for change.

Principle 7: The Helicopter Test

We once worked with a consultant on an impact evaluation project who used a great hypothetical question:

“Whenever I’m assessing the benefits of a program in the developing world, I ask myself; would people be better off if we’d have gone up in a helicopter, taken this money and scattered it above the town?”

It’s a showstopping question, and in that specific case we all knew the answer – the project we were assessing would have been much better off throwing their $300,000 budget out of the helicopter.

That’s damning of the organisation’s recipe for change.

If our recipe doesn’t create something better than the most basic alternative, what are we doing? That would suggest the ingredients, funds and resources would be better spent going directly to your beneficiaries, or at least to your competitors.

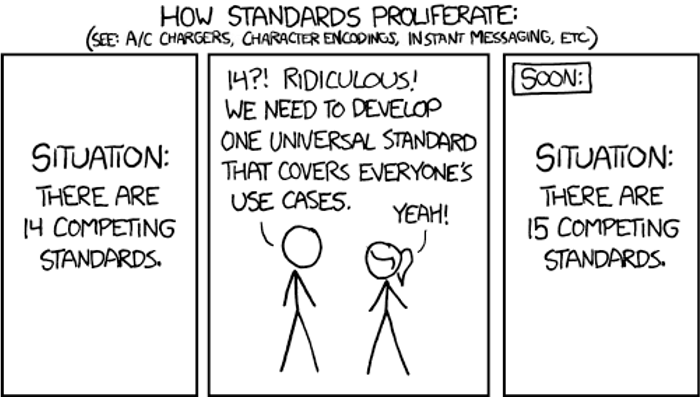

Principle 8: Standards Don’t Tell The Full Story

Hopefully this changes, but we can’t think of a time where we’ve heard someone say “we found these new measurement indicators and standards to be really helpful for our work”.

xkcd captured it beautifully:

Standards are tricky because the social enterprise or impactful business field isn’t really one industry, it’s a collection of industries that aren’t easily compared.

It would be hard to say “this program to help save Koalas is 2x more impactful than this program to encourage more girls to study in STEM”.

How can you compare carbon capture against anti-racism campaigns?

It might not even be fair to draw comparisons within a niche field – should all of the funding flow to the “most efficient” projects in a certain country?

These have been attempted to be captured with tools like the Social Return On Investment (SROI), which highlight how much “benefit” is created per dollar of funding.

The catch is, these aren’t meant to be compared against other fields, but rather help you track improvements year-on-year in your own work (or maybe against a direct competitor).

And yet, it’s hard to not draw comparisons when you’re applying for the same grant funding, bidding for the same tenders, or pitching to the same social enterprise consumer.

They feel like a good idea, but it’s unclear how much the audience can conclude from this information.

The other problem is that a creative person can use selective data to paint whatever story they want.

Consider Actor A and Actor B, and tell us who you’d rather meet for dinner:

Actor A has been repeatedly named as “One of Hollywood’s most bankable stars”.

Their movies have generated over US$9.3B, they won an Academy Award in 2022, and have also won four Grammys over their career.

They earned the highest-paid movie role of all time, when they reportedly earned $100 million.

Their recent film was sold to Apple Studios for $120 million in June 2020, which made it the largest film festival acquisition deal in film history.

They also won the award for outstanding actor at the 2023 NAACP Image Awards.

Actor B has been in the news for the wrong reasons.

Their positive Q score has drastically fallen 39 to 24 in 2022, and their negative Q score has jumped from 10 to 26 (the industry average is 16)

They have had several high-profile box-office failures in the past 5 years.

They famously turned down the lead in a major movie franchise, in order to make a movie with an IMDb score of 4.9.

They are guaranteed to not attend future academy awards.

Actor B appeared in one movie in 2022, and is not starring in any movies in 2023.

Who would you rather meet?

Before you answer, we should probably mention that both Actor A and Actor B are Will Smith.

What you highlight and what you omit drastically change the story.

It’s why we need a healthy level of scrutiny of the methods we use to measure performance, to see if we’re having the wool pulled over our eyes.

Be wary when someone wants to use bizarrely specific metrics to show their work, it might be an attempt to camouflage the real story.

Principle 9: Know Your Readers.

Social entrepreneurs, like all marketers, need to know who they’re talking to.

This changes the terminology you use, what you choose to highlight, and what you assume they already understand.

Specifically, we want a sense of what is most important to them, and what information they use to make a purchase decision.

Your funders care about:

· Behaviour change work

· Systems change work

· Behaviour change stories

· Systems change stories

They want to see that good work has happened, and they want to be equipped with evidence and stories that they can share with their network.

All four of these are necessary; the work without the story will be hard to sustain, and the story without the work is basically fraud.

We want to understand what funders need to see and hear in order to create a new funding opportunity.

Is it particular metrics?

Is it a human story?

Is it a compelling case study?

Is it a value-for-money statistic?

Your customers care about:

· Your products

· Your outputs

· Your outcomes

· Stories they tell themselves and others

It’s nice to tell yourself a story about how you’ve made a contribution to a cause, but a story can’t outweigh a bad product.

The impact story only matters to the customer once they’re satisfied that they got what they paid for, or else they won’t come back again.

Customers are also too skeptical to accept an impact story without understanding the steps between their purchase/consumption and the outputs/outcomes from your business.

e.g. World Vision’s Child Sponsorship program made this hyper-clear by saying “you can sponsor a child for $1 a day”, and sending a hand-written letter & photo.

The customer has a vivid picture of their contribution, and is likely to stick with the program for years to come.

The fact that child sponsorship doesn’t actually work like that is irrelevant (your money doesn’t literally go towards that one child), the warped story for the customer seems logical and is emotionally compelling.

Your end users care about:

· Reducing their risk

· Saving money

· Fitting in with their chosen groups

· Improving their quality of life

· Doing the right thing for their family/community

People can drag their feet if they’re not excited, educated and on board.

Well-intentioned programs fail to catch on because they aren’t trusted or understood by their end users, even if the offers are genuine.

Even if your offer is free, you are asking for buy-in.

You are asking for people to change, and they hate change.

They are unlikely to take your word for it, and will need to be persuaded to try something new or stop doing something that they believe is harmless.

Almost every “good” social change has been met with resistance, e.g. seatbelts, drink driving rules, bike helmets, restrictions on smoking, etc.

Social change can’t rely on punishments to motivate new behaviours, it also needs to educate and persuade people to switch their habits when no one is looking.

What will change their minds?

It might be a visceral demonstration, it might be hard-hitting statistics and stories, it might be evidence that everyone else is already doing the new behaviours.

But if your recipe for change isn’t clear to them, they’ll undermine your efforts.

Principle 10: Practitioners are worried about survival, not perfection.

Pablo Picasso famously said:

“When art experts get together they talk about structure, and form, and meaning.

When artists get together they talk about where to buy cheap turpentine.”

Practitioners often don’t have the luxury of talking about optimisation and ethical perfectionism, not while they’re stressed about covering next month’s payroll.

They agree that they want to do as much good as possible, but that probably involves staying afloat for the next two years.

If the project can stay active for 10 years with moderate social outcomes, it has the chance to do a lot more good than one with impressive social outcomes that burns out in 18 months.

This comes back to the Three Buckets – Cash Cows, Small Margin and Loss Leaders.

Social entrepreneurs need to watch their balance of these three, ensuring that the see-saw tips towards the left.

There are no strict rules, but in a lot of cases the Loss Leader projects have more freedom to create positive change than the Small Margins or Cash Cows.

However, the Cash Cows are what give you the stability and resources to fund the Loss Leaders.

This partially explains why social entrepreneurs are so keen to set up cafes – nobody would argue that cafes are the best way of creating social change, but they are a known quantity, they are sustainable, they create employment and visibility.

The café becomes a “home base” for the rest of the organization, who are then able to take more risks and fund more loss leaders.

The Helicopter Test is relevant here - $100,000 on a new Cash Cow business unit is likely less impactful than $100,000 out of the helicopter.

But that Cash Cow business might be able to generate $50-70k of benefit per year, every year, in which case it’s appealing.

On the other hand, if the Cash Cow turns out to only create $12k of benefit per year, then it becomes an ineffective distraction, and you’d be better off doing something else.

That’s the “cheap turpentine” conversation for practitioners.

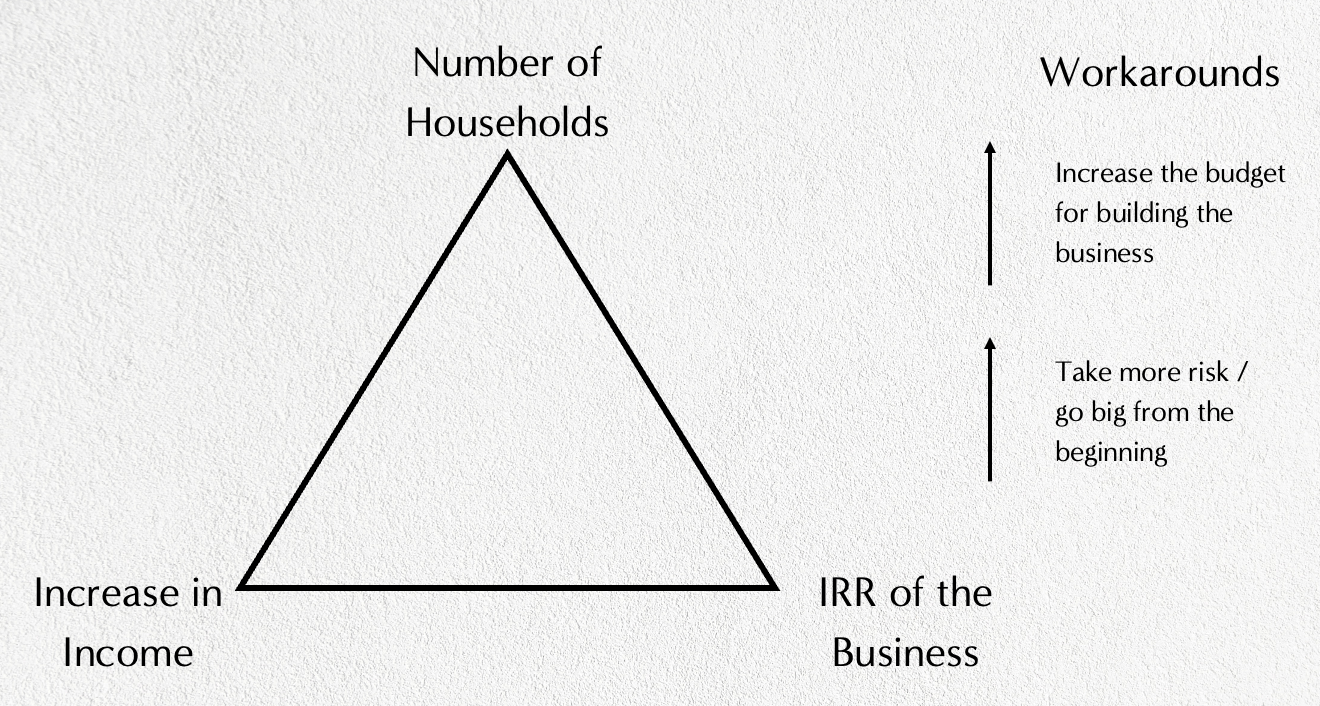

Principle 11: Embrace Your Trade-Offs

They say that “Trade-offs are the essence of strategy” – the important choices are the ones where you decide what NOT to prioritise.

It is impossible to be all things to all people, and some choices rule out others.

You’ve probably seen this with trade-off triangles like “Good-fast-cheap; pick any two”.

There’s one for university too: “Good grades, good sleep, good social life; pick any two”.

For an inclusive agri-business in the developing world, the triangle becomes “Number of households affected, increase in income, viability of the business”.

We can work with a lot of people to give them a small boost, or a few people to give them a big boost, or a lot of people to give them a big boost but the company will have no margins and no reserves.

There are two “cheat codes” to avoid this dilemma:

You can increase the budget for building the business, covering your overheads so that you can pass on the maximum income to farming families.

Or you can take more risk and build a really big business from Day 1, benefitting from economies of scale.

A funder can help with these “cheat codes”, but in return they’re going to want data and stories on exactly how their resources benefitted the community.

The same applies to Food Hubs, where the three points on the trade-off triangle are affordability, farmer incomes and retained earnings in the business – pick any two.

Again there are cheat codes; find a pool of grantors and subsidies, or go big from Day 1.

Every new food hub or player in the ecosystem gets to decide what they will never do, and where they’re willing to compromise.

When push comes to shove, someone pays for your food, either the farmers, the businesses or you.

Your industry probably has a similar set of trade-offs, and it’s worth thinking about how you’ll handle them.

This helps you identify which factors are the most important to you, which are the factors that will need proper measurement.

Principle 12: Measure to learn, measure to fix.

“Metrics are for doing, not for staring.

Never measure because you can.

Measure to learn.

Measure to fix.”

- Stijn Debrouwere.

There’s a compatibility issue between the worlds of Impact Measurement and the world of Entrepreneurship.

Impact measurement, by definition, takes a long time and is murky to process.

In a lot of cases, it can take years to see the full impact of an initiative or project.

And even when we have the data, it’s hard to attribute which results came from the initiative and which came from other factors.

Entrepreneurship, by definition, is about managing uncertainty and making rapid improvements to our work, usually through experimentation and iteration.

So the social entrepreneur can’t afford to wait for their impact measurement to come back with answers, they need earlier signals to show them how things are going.

That means measuring activities and outputs, rather than impacts, or using a handful of stories to gauge their outcomes, rather than conducting more detailed measurement.

If the metrics you track aren’t prompting you to change your work, then they might be the wrong metrics.

A helpful distinction is the difference between Leading and Lagging indicators.

Leading indicators refer to the work you’re putting in, whereas lagging indicators show you the results of your work.

e.g. if you’re learning the piano, leading indicators might describe how many hours you spent practicing or how many lessons you’ve taken. Lagging indicators might describe how many songs you can play, or which “grade” you’re up to.

Both are helpful, because without either of them you don’t have a full view of your progress.

In the book The Four Disciplines Of Execution, Sean Covey and Christ McChesney wrote:

“Lag measures are ultimately the most important things you are trying to accomplish.

But lead measures, true to their name, are what will get you to the lag measures.”

Most impact metrics are lagging indicators, but these need to be paired with leading indicators, and that’s most likely going to be activity metrics or output metrics.

So someone like Keep Cup will be watching lag measures like “number of disposable cups going to landfill each day”, but the lead measures in their control are more like “number of cafes stocking Keep Cups” or “Cups sold each day”.

Practitioners need measures they can act on.

It’s probably better to have imperfect measures like outputs and outcomes to guide your actions immediately, while you wait for longer term measures to become available.

These help you focus on lead measures, which you can wake up and influence each day.

Done is better than perfect.

In summary:

• Measurement is great when it’s connected to either improving a recipe for change, or for telling compelling stories to funders and customers.

• Obsessing over lagging indicators and ethical perfectionism is a luxury that you can do if and only when you have financial security.

• Learn the language and metrics of your audiences, so that you can persuade them to take an action rather than give you a vague compliment.

• Find the lead measures that are within your control and are likely to lead to positive social outcomes, then prioritise them each day.

• Most funders are looking for competence, clarity and accountability, not the perfect metric.