What Is A Venture Backable Business?

In a previous post we looked at the startup industry, including some definitions and examples of what separates startups from small businesses, and what investors usually look for.

If you didn’t read it, we can broadly summarise it as:

· A startup is a company looking to grow fast, with great skills of offense (finding, delighting and converting customers) and defence (fighting competitors, avoiding bankruptcy and implosion).

· They often use technology to grow quickly, but they’re not all tech companies.

· They often need outside money from investors, and those investors usually have high expectations.

In this article, we’ll explore those investor criteria in more detail, to understand what makes a startup “Venture Backable”.

Movies vs Blockbusters

If starting a company is like making a movie, then a Venture Backable company is like the word “Blockbuster”.

A blockbuster is a movie that earns a lot of money, is very popular and becomes a household name.

They usually feature famous actors, or they make their actors famous.

These days, a blockbuster would probably earn close to $1B in revenue.

Studios love blockbusters, far more than they love smaller projects that might be better works of art – much to the dismay of the film community.

And you can understand the financial motives – trying to create a billion-dollar hit is more lucrative than a $20m movie that makes back its budget.

Better yet, there’s often a push to turn the initial hit into a franchise, with more $1B+ movies to follow, as well as all sorts of merchandise and licensing arrangements.

So when a studio sets out to create a blockbuster, they’re probably going to want to control a lot of the development process, influencing each step to increase their chances of a big financial success.

The directors, producers and stars of these films understand the deal – less control, in exchange for the funds and guidance towards becoming a huge moneymaker.

None of this suggests that a blockbuster is the “best” type of movie, and studios have lots of misses for every hit.

But we do know about some of the elements that blockbusters usually have – a love story, action sequences, well-liked actors, international appeal, etc.

Venture Backable businesses are the same.

They’re all different, but with some recurring themes that enable them to grow quickly and delight a huge audience.

The opposite path can be great as well – you might be making the equivalent of an independent film, and that might be brilliant.

You probably have a higher chance of winning an Oscar, but also less chance of making $1B+.

You don’t have to love Venture Capital, but you should understand it

The startup world tends to celebrate investment and investors, and that can make some entrepreneurs idolise the process of raising money.

Money is not good or evil, it is fuel.

That fuel can make a good smaller business into a good bigger business, or it can make a broken smaller business into a broken bigger business.

There’s a sense that it can turn a broken smaller business into a good bigger business, but these cases are rare.

It can definitely turn a good smaller business into a broken bigger business, especially if you work with the wrong investors on the wrong growth initiatives and wrong priorities at the wrong time.

Venture Capital is a distinctive sort of investment style – one that is seeking big opportunities and isn’t afraid of big risks.

These investors want you to succeed, so that they can sell their share of your business for a huge profit, giving you both some skin in the game.

Your alignment is based on a shared interest in massive growth – if that’s not you, then the world of Venture Capital might not be the best fit.

However, the key criteria these investors use are interesting – certain numbers, metrics and aspects of a business that give it the best chance of massive success.

“Venture Backable” means that you could hypothetically go on Shark Tank and answer the Sharks’ questions.

The Sharks may or may not make an offer, and you may or may not accept it, that’s up to each of you, but being able to explain your thought process and having thought about their criteria will make you sharper.

Even if you’re unlikely to approach a “Shark” for money, it’s helpful to understand what they look for and ask good questions of your own company.

This list of considerations is not an exam, they’re not all mandatory, but they are generally good things for a startup.

The beneficiary of this process is YOU, so there’s no point in cheating.

Be honest, keep track of whatever you don’t understand, and ask yourself good questions.

The aim is to have this conversation with your ideas, think of options and strategies, and gather evidence and metrics before someone asks

If you can’t show your working out or have no basis for your sense of the future, you risk having frustrating and unsatisfying arguments with investors.

They might still be skeptical of your numbers and assumptions, but at least you’re speaking the same language.

Where is there a golden opportunity?

As we’ve previously seen, startups are looking for gold: a deep pool of customers with a serious need or interest – they want to buy something that solves a valuable problem, or buy something that genuinely delights them.

Just like in nature, we aren’t creating gold, it’s already there in the ground; we’re looking to find it and extract it.

There are two ways of finding gold:

The first is to identify areas that are geologically likely to contain gold, they have the necessary pre-conditions for gold to form.

In entrepreneurship, this is about understanding the trends and demands that lead to customers with High Value Jobs:

· More people suddenly working from home

· Tech company layoffs

· A renewed interest in taking climate action

· New leaps in generative AI

· Couples who have just become engaged

· Millennials feeling like their careers are stuck

· Brands struggling to keep up with social media changes

All of these feel like they might contain gold, but it’s not apparent as to how much there might be, or how easy it will be to mine.

They are intriguing and have potential, but are not guaranteed sources of startup gold.

The second way is to get out your metal detector, to see if there’s anything beneath the surface in one specific area, and probably an area near you.

In entrepreneurship, this means talking to real customers about real problems, to understand how they think and how they behave.

These are people with strong desires or strong complaints, who have looked for solutions and are ready to take action.

This might be you scratching your own itch, addressing a problem you have in your work or life.

It might be a friend or family member, or something that has come up in your workplace.

e.g. your boss is afraid of AI, your freelancer friends hate making their own websites, you have choice paralysis with streaming services, several of your friends are now starting to have back pain.

As Yee Tong said “Whenever you hear yourself bitching, you’re identifying a market need”.

But for an opportunity to be Venture Backable, it needs to be BIG.

It needs to be exciting and lucrative, meaning it affects a large number of people, who are (reasonably) easy to sell to.

In gold terms, this is looking for the future site of a gold mine, not a modest operation searching for gold nuggets.

There is absolutely nothing wrong with hunting for gold nuggets, and there’s nothing wrong with profitably serving a small market - it’s just not the game the VCs are playing.

Like a miner, you’re digging down to get to something valuable, in this case with the “Five Why’s” or the roots of a Problem Tree, to understand what is truly bothering customers and creating such a big opportunity.

Behind every decision are two reasons – the good one and the real one – and so in a lot of cases, a customer’s true motive for doing something new might not be nice to say out loud.

That’s fine, our job is to understand our customers, not judge them.

Who’s the customer?

Customers aren’t just another word for “people affected by the problem”.

We’re specifically referring to:

· People with a motivation

· People who have decision-making power

· People who are spending money or giving up something of value

These customers might be sophisticated (they know what they’re doing, they’ve bought this before) or unsophisticated (in need of some guidance and advice).

They might also be the end user or the beneficiary, but they might be separate (e.g. a manager making a choice that affects her entire team).

They might be spending their own money or company money, and that usually shifts their criteria and deal-breakers.

Even in a B2B environment, we are always selling to a human, who is acting on behalf of a brand, and we need to thoroughly understand that person.

· Are they also the end user?

· Have they bought this before?

· What are their criteria or “Jobs To Be Done”?

· Is there a deep pool of customers like them?

· Are they reachable?

· How much do they care?

If there aren’t many of these people, if they’re not excited by a solution to their problems or if it takes too much time and energy to convert them into paying customers, then this might not be the basis for a Venture Backable startup.

What else exists?

You won’t like to hear this, but your idea has either:

· Been done by someone else, well

· Been done by someone else, poorly

· Never been thought of before

· Been thought of but deemed impossible or irrelevant

For this reason, you’re going to want to research which of these categories (yes, plural) you fall into.

Don’t go around saying “this is radically innovative because…” if you haven’t taken the time to check if that’s actually true.

This is doubly true when dealing with VCs, who have likely heard of more projects, startups and innovations than you, and they absolutely love correcting you in public.

Having said all of that, your work does not need to be totally new in order to be valuable.

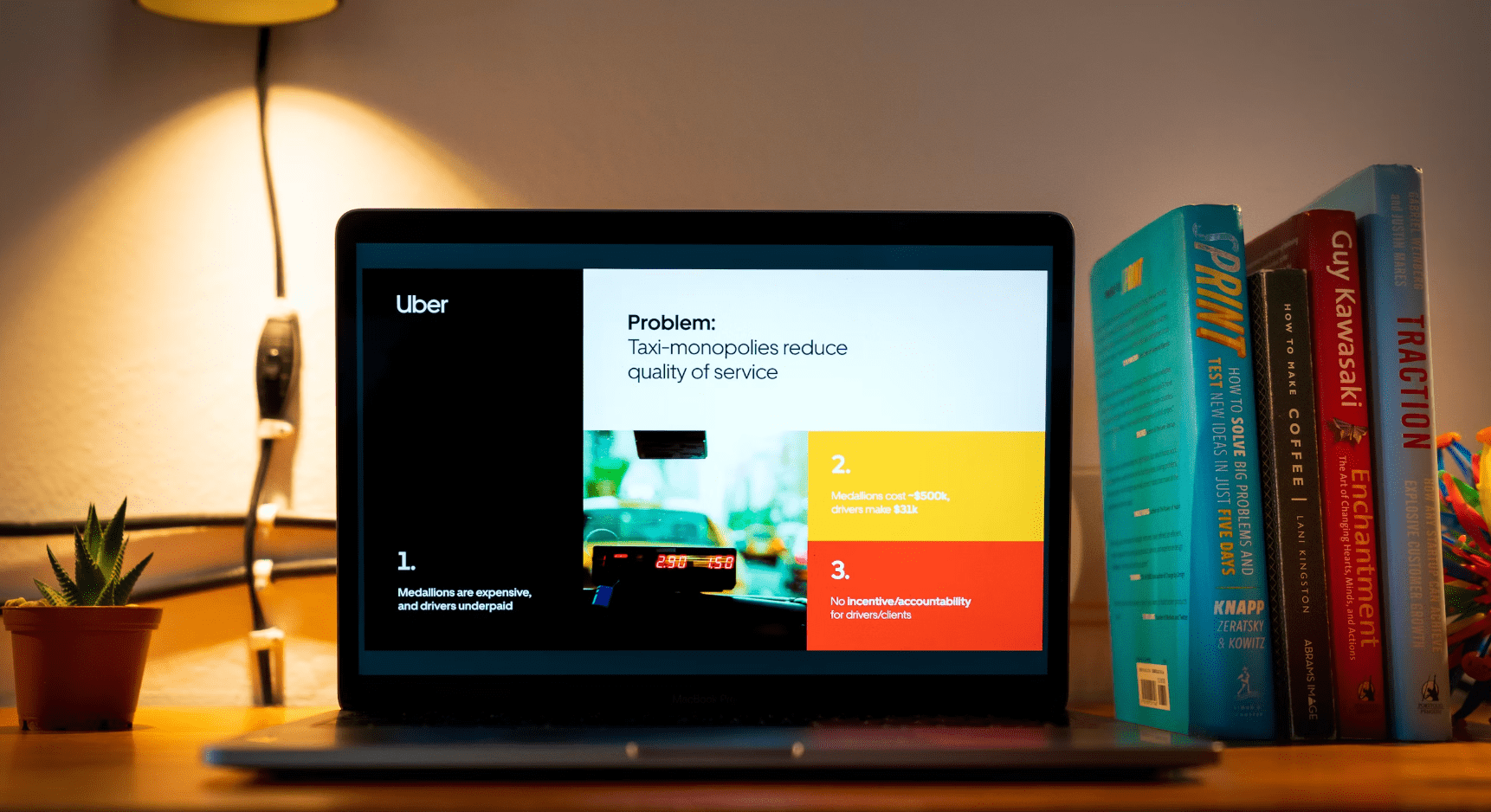

It can be a radical innovation (ChatGPT or Amazon), an incremental improvement (the iPod or Canva), or a combination of existing ideas/features in a new setting (e.g Uber or Bumble).

The important detail is: how much better are these than the competition?

Radically different is only good if it’s significantly more desirable or more effective, to offset the switching cost of the customer having to try something new.

There is no strict rule here, but you’ll hear VCs talking about wanting to see solutions that are 10x better than their rivals.

History and comparisons are notoriously hard in startup world, because so many good ideas die because they came up at the wrong time:

· Zoom would not have been adopted like it was if not for the pandemic.

· Netflix had the idea for streaming movies before the technology was ready.

· Canva would not have been as needed before every brand needed to create social media content.

· Electric cars have been a concept for decades, but without strong batteries, their appeal was limited, and autonomous cars are stuck in the same limbo today.

All of these are difficult to predict, and that’s why investors treat their investments like bets.

An idea might succeed or fail for reasons they could not have possibly predicted, but you’ll only be able to win if you’ve got a company in the market.

Back of the envelope numbers – is there a lucrative opportunity?

Venture backable companies deal in big numbers, most of which are not verifiable and are basically a series of guesses.

And somehow, that’s sort of ok, so long as those guesses add up to a lucrative big number at the end?

That’s because these conversations are all about “order of magnitude” – how many zeroes are on the end of the number.

e.g. how many companies would buy our software: is it around 50 or 500 or 5,000 or 50,000?

Are they paying subscriptions of $30 or $300 or $3,000 or $30,000 a month?

That’s what creates an appealing opportunity – the chance to take a dominant position in a huge market.

And so for the first few years, profitability is seemingly less important than growth potential, so you can expect to hear lots of analogies around “taking a smaller slice of a much bigger pie”.

For this reason, you’ll often have discussions around the Total Addressable Market (TAM), Serviceable Addressable Market (SAM) and Serviceable Obtainable Market (SOM).

Investors want to see that this is a multi-billion-dollar industry, and that you can obtain a decent-yet-realistic piece of it in the first few years.

Then there’s the Unit Economics: how much money do we make per customer and how much do we spend in acquiring/serving that customer?

The specific calculations are different depending on your industry, sometimes it’s good to look at your retail price and your cost of goods, to determine your gross margin.

Other times it’s good to look at your Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC) and your Customer Lifetime Value (LTV), to see if growth is costing or earning you money.

Again, there are no strict rules on what investors want to see, and there are scenarios where a funder might be happy to lose money in order to establish dominance and shut out competitors.

The important thing is that you know your numbers and have thought about your options.

If you’re wondering “what specific numbers and options might those be?”, a good starting point is what Noah Kagan calls the six revenue dials:

· Order value – can we increase how much customers buy at a time?

· Frequency – can we encourage/incentivise customers to come back more frequently?

· Price – can we charge more for what we sell, or charge less and attract higher volumes of customers?

· Customer Type – can we attract and serve more lucrative types of customers?

· Product Lines – can we add more products that would entice additional customers?

· Add-on Services – can we offer relevant extension services that customers might appreciate?

The crucial detail for venture backability is: Is there a pathway to profitability?

It doesn’t have to be from day 1, it doesn’t have to be guaranteed, but if there’s no profitability on the horizon, it will be a very tough sell for both the investor and for yourself.

How will this unfold?

People will often say things like “Ideas are the easy part” or “Ideas aren’t worth much, what matters is the execution”.

They’re not wrong, but execution is hard to predict.

As Henry Ford said “You can’t build a reputation on what you’re going to do”.

An investor will be on the lookout for an unfair advantage – something that gives you the ability to outperform competitors, such as:

· A patent

· A scarce resource or exclusivity over something valuable

· A big head start, either by going first or having existing assets

· An existing brand and good reputation in the market

· Trade secrets and knowhow from having done something like this before

· A high performing team (more on that later)

Of course, all of these advantages might help you attract lots of attention and customers, but that can create other catastrophes, specifically if you can’t grow at a fast enough pace.

Broadly speaking, all of the systems, infrastructure and “glue” that holds a startup together tends to break each time you triple in size.

e.g. your methods for hiring and firing, the way you set and monitor your team culture, how you stay in touch with customers, how you fulfil your orders, how you launch new features and products, etc.

What works at one size will be woefully inadequate at a larger one.

This has the vague title of “Scalability”: Do we have the systems and assets to repeat our successes?

Did your strength come from local relationships and a deep understanding of that country’s business culture?

Do your suppliers have the ability to offer great results at 50x the current rate?

Does everyone in the team need to talk to you each week?

All of these sound do-able on paper, but talk to anyone who’s tried to scale a business and they’ll tell you about the realities and shocks that caught them by surprise.

Then there are your competitors.

Even though they may have never thought about doing what you’re doing, or they deemed it too hard or too niche, if they see you making a large profit they’ll try and replicate your success.

Or as Jeff Bezos put it: “Your margin is my opportunity”.

That might come about by creating something cheaper, something for a different niche, or integrating some of your good ideas into what they’re already selling.

Maybe they’ll be even more brutal and try to fight you for your spot in the market, going after your customers with a similar offer to yours.

Investors love talking about this like there are barbarians attacking your castle, and that what you need is a “moat” – something that makes you hard to attack, and that makes your startup defensible.

This is your competitive edge, something that disincentivises other companies from fighting you directly.

Remember, if you’re trying to tell the investor that this is a billion-dollar opportunity, then competitors are inevitable.

These might be other startups, even ones that don’t yet exist.

They also might be massive companies that see an opportunity to build on your good work and outgun you with their resources.

Either way, you want to think through your plans for taking on competitors, without being paranoid and letting it stop your growth.

Assumptions, Traction and Validation

Of course, to discuss any or all of the above issues with an investor is going to involve assumptions – you are doing something new and different, and that means making guesses.

Guesses aren’t bad, they’re inevitable.

But there are two risks: we make an assumption without checking it, or we make a detailed plan around that assumption without running a test.

The first category of assumption – the ones we don’t think to check – are dangerous because they sneak up on you.

These might include:

· No one else has done this/is doing this

· We can easily find customers with pain points

· Customers know what they want

· Customers will happily pay for solutions

· We can attract top talent to our team

· Customers can easily pay $XX/month

· Demand in other countries will be similar to demand here

· We can add users for less than what they pay us

Founders look at these with bemusement and sometimes disdain, and the words “Well of course we know that..”.

Maybe in most cases they’re right, but being wrong on any of these massive assumptions will pull the rug out from underneath you.

The second category of assumption is the ones with detailed hypothetical plans.

They feel smarter because the founder has taken the time to formulate strategies and write up their processes.

Steve Blank said “No plan survives first contact with customers”.

Customers will surprise you, in terms of who they are, what they care about, how they shop, what they’re willing/able to pay, and how much they’ll actually utilise the products and services they buy.

So if you can tell an investor “We already have 50 customers using this today”, that gets taken very seriously, despite 50 being a small number compared to the total addressable market.

It shows that you’ve got an appealing offer, that you can sell, that customers do exist, and that you’ve probably had a lot of learnings so far.

This is called “Traction” – tangible signs that your work is desirable, feasible and viable.

It puts fears to rest, it settles some (but not all) silly debates, and it gives you a real sense of momentum.

This validation is so valuable, and it’s why we say that experiments are your friend.

The best time to find out your assumptions are wrong is right now, when changing them is (comparatively) cheap and fast.

We want experiments that show us the truth, we don’t want to cheat.

And a VC will want to see evidence of desirability from customers and their actions, not evidence from your colourful, pristine pitch deck.

Where might we pivot in the future?

Because of the high-risk nature of venture capital, investors are going to seek assurance that this isn’t an “all or nothing” proposition.

So many great and successful startups came about as a pivot from an adjacent idea.

Pivots, like moving your feet on a dancefloor or netball court, involve keeping one foot planted and the other moving freely.

You end up in a similar spot, but facing a different direction.

In this case, a pivot might include:

· Targeting a different customer

· Focusing on a different customer problem/Job To Be Done

· Selling a different product/service

· Using a different revenue model

· Diversifying into a broad range of offers

· Narrowing down to one hyper-specific offer

Not all of those options remain venture backable, but the idea of being able to pivot when necessary, or pivoting because a better opportunity reveals itself, is incredibly desirable.

Who’s on our team?

An investor is not only betting on your idea, they are also betting on an implementation team to do the work, make improvements and adjustments, or even drastic changes in the future.

They are betting on your responses to success and failure, and so they’ll want a good sense of who you are and what you’re good at.

In particular, they are looking for the combination of passionate and capable; one without the other won’t be enough.

They want to know that you have the right people on board, and that those right people are invested in the success of the company.

Skin in the game is a powerful motivator, it reduces the chances of people flaking away, and gives the company some continuity.

Interestingly, a great team can be made up of a broad range of people, whose skills and strengths might balance each other’s weaknesses.

Your product experts don’t have to be public speakers, your CFO doesn’t have to have first-hand experience with the problem, you don’t have to be Silicon Valley tech bros.

We want to see a strong track record, a sense of momentum, and confidence that you’re not going to ruin a good business with culture problems further down the track.

You can also talk about your board, advisors or coaches – if you don’t have a track record, can you benefit from the wisdom of those who have been in your shoes before?

If your work is not venture backable, you can still build a remarkable company and make a lot of profit.

The same principles still apply, but they might not need to be so extreme.

If you want venture funding, incorporate these key elements into your designs as early as possible.

Learn the language, aim for a problem with huge upside, and create systems that won’t have bottlenecks that limit your growth.

Most importantly, listen to a wide range of stories, from those who chose the venture path and those who didn’t, and those who had lucrative exits and those who didn’t.

When you’re ready, it’s time to work on your:

Origin Story

Problem Tree

Customer Personas

Testing Plans

Unit Economics

Business Model Canvas

Brand Strategy

Sales Principles

Pitch Preparation