The “What’s In It For Me?” Guide To The Design Process

You’ve probably heard about terms like “Design Thinking”, “Human Centred Design” and “Lean Startups”, and for good reason; these new methodologies bring in some clunky terminology, but they are the real deal.

The genuinely work, they can help you create better businesses, they will save you time and money, and can be used across all of your current and future projects.

The catch is, a lot of the articles out there are tough to read.

The language is unfamiliar, the tone is too academic, and there is an alarming lack of examples in their explanations.

Having taught this process to over 935 founders, we’ve seen so many people use these tools to great effect, once they saw that it was worth investing their time into learning something new.

That’s what this guide is for – to explain the philosophies, tools and habits of the design process, with a specific focus on why this will help your business this year.

If we’re going to understand the new way of starting a business, it’s helpful to start by examining the old way of doing business.

It made a lot of people a lot of money, but also had some fatal flaws…

The Old Way Of Starting A Business

Until quite recently, the process of starting a business went roughly like this:

· Have an idea for a business that doesn’t yet exist

· Research the market to see if anyone else has done something similar

· Declare that the absence of a direct competitor is “a gap in the market”

· Conduct focus groups with customers to pitch your idea and measure their responses

· Create a Business Plan, featuring financials, marketing plans, role descriptions, segment analysis, and some very hopeful growth charts that you have labelled “conservative estimates”

· Take this plan to funders, be it a bank, local investors or your own money

· If funded, set up shop and get ready to start selling

· Launch the new business with great fanfare

Then either:

a) Make a lot of money, pay back investors and start looking at expanding the company

b) Limp along without much idea of what you can change to find more success, or

c) Run out of customers or funds, sell the remaining assets and close the business

This process was successful for several reasons:

1. It’s very time efficient, jumping straight from a winning idea to a proper business

2. It makes the founder think through the entire process before making a financial commitment

3. A business plan is helpful for investors, creating a compelling picture of the future business for them to assess

Now while that’s all true, it’s also only tells half of the story.

Let’s examine those success factors in more detail:

1. It’s very time efficient IF you have a winning idea. If you don’t have a winning idea, you won’t know until you’ve invested a lot of time and money

2. It makes founders think through the entire process, but they are often working from a place of ignorance, and make linear plans that aren’t representative of what running a business is actually like

3. A business plan impresses an investor, but is a work of fiction. Worse still, because they’re tedious to re-write, founders are reluctant to change their plans even when evidence suggests some flaws or an alternative way of working.

For this reason, we had a lot of success stories come out of this process, but a much larger number of failures.

The percentages we were taught at business school were that 50% of new businesses would close in the first year, 70% by year 2, and up to 90% by year 5.

And pre-internet, you weren’t hearing the stories of the businesses that failed in the first two years, you only heard interviews with the 10% that survived.

A New Way Of Thinking

Luckily, it doesn’t have to be this way.

Today we approach things a little differently.

We’ll first look at the philosophical differences, then some of the practical tools and frameworks.

Here are some alternative perspectives:

· Instead of trying to jump straight to a genius business idea, what if we thought like a designer; researching problems and customers to understand what they truly need and want?

· Instead of planning every detail, what if we took our initial concepts and made them tangible, like a prototype?

· What if we tested our ideas and prototypes with customers without spending much money, so that we could learn without letting our emotional/financial investment bias our thinking?

· What if we explored several versions of our ideas, and only put in more energy/money when we saw real interest from the market?

· What if we launched without much expense, and kept adapting the business as we learned more about the industry, our capabilities and our customers?

This approach is sensible, but it does take longer and can feel murky at times.

It forces us to admit that we don’t know everything, but also lets us make several iterations (or versions) of our business ideas before we need to make a big commitment.

Instead of an all-or-nothing result, we create businesses that are constantly learning and evolving, running lots of tests, doubling down on the ones that show positive signs and squashing the ideas that fall flat.

That takes more patience and creativity, but it drastically reduces the risk of major failure.

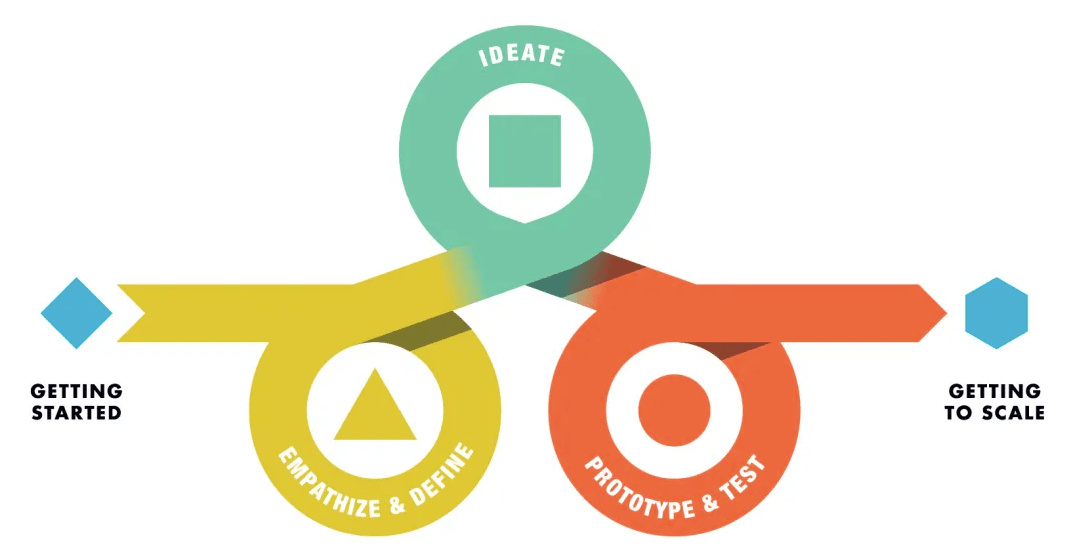

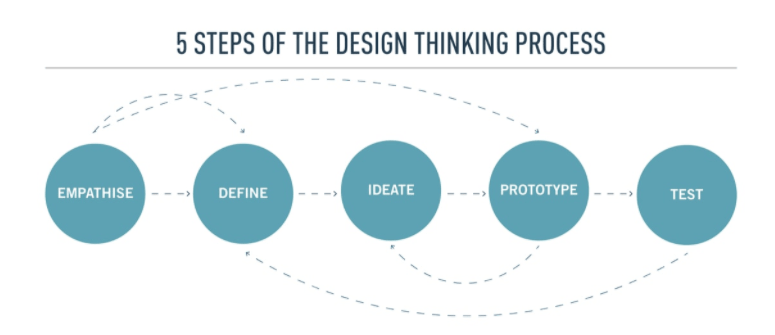

Here are some diagrams that show the process:

nextleapdesign.com

careerfoundry.com

You’ll notice that a lot of these diagrams have loops or curly arrows, whereas old fashioned business diagrams are full of chevrons and straight lines.

That’s because the design process accepts that we’ll need to try some of these steps a few times until we find something that works.

That’s not a flaw, that’s part of the process – trying lots of options until one “clicks”.

You’re probably not a genius with the gift of prophesy, and luckily you don’t need to be.

The aim is to keep going, making lots of versions until you find one that is proven to work.

The first ideas that pop into your head aren’t often the remarkable ones, so this process encourages you to generate lots of ideas, even ones that sound weird or silly at first.

And while you might feel impatient, it means you’ll go to funders with evidence, momentum and real revenue, which are far more persuasive than a fictional business plan.

The Double Loop

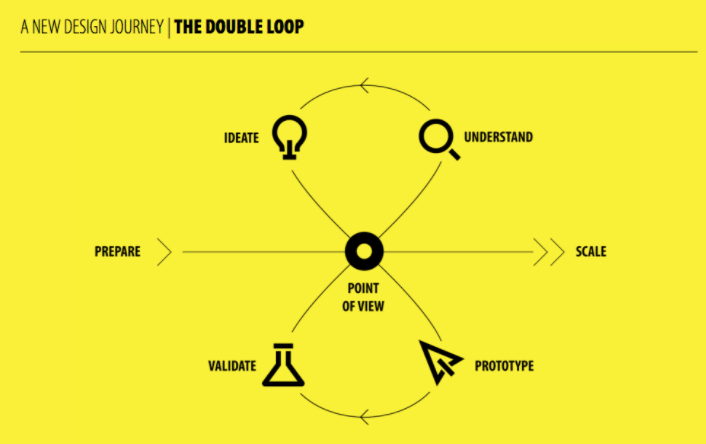

One of the most realistic diagrams of what happens in this process is The Double Loop:

designabetterbusiness.com

The top loop is when you’re thinking and dreaming up new ideas or new products/services, the middle is your ever-evolving point of view, and the bottom loop is when you’re building prototypes and testing them with real customers.

Each loop changes and improves your point of view, and they make each other better.

Theoretical work is made stronger by real-world experiments, which in turn spark new ideas or add more nuance to your thought process.

The aim is to go through the two loops as many times as necessary, improving the quality of your ideas until you have something that customers appreciate.

Some people would like to proceed before they hit that milestone, but that won’t serve them well – if the idea isn’t working, why would you want to scale it up or pitch it to investors?

This is innovation, and innovation doesn’t come with guarantees.

Yes it would be great if there was some sort of assurance that “if we do two rounds of testing, we’ll definitely come out with a winning idea”, but the real world doesn’t work that way.

This is where a new entrepreneur has an edge over their bigger rivals – you can afford to take risks and to be creative, whereas their product managers are terrified of trying something that might not succeed.

If innovation was predictable then big boring companies would have mastered it, but they haven’t, and that creates an opportunity for you.

A lot of ideas need time to evolve, so this process is hard to do in a hurry or when under extreme pressure.

If you need urgent cash, this isn’t the process for you.

The Double Diamond

Another helpful diagram is The Double Diamond, originally created by the UK Design Council.

It describes the two main stages of work, with four steps that each start with “D”.

designcouncil.org.uk

The first diamond is “Discover” and “Define”.

In the discovery phase, our job is to look at lots of different problems, learning about the field and how hard it has been to create meaningful change.

We want to understand the broad range of challenges in this industry, and how they might tie in together.

The define phase is the process of narrowing these problems down to a single statement, one that sums up the part of the problem that is most pivotal or most interesting to you.

It reminds us that we realistically can’t solve every problem at once, and need to prioritise the most influential work in order to gain momentum and credibility.

Right here in the middle, we have our problem statement – a short summary of the problem we are committed to addressing.

It shouldn’t be too vague, and it shouldn’t be too specific in describing your exact business model.

The second diamond is “Design” and “Deliver”.

In the develop phase, we once again go broad in looking at potential solutions – weird ideas are not only permitted, they’re genuinely helpful.

We want to create a long list of potential options, trying not to rule anything out too quickly, until the ideas have had time to state their case or show their value.

In the delivery phase, we once again narrow the field, selecting one or two initiatives to take forward.

You don’t need to “kill” the other concepts, but you’re deciding not to prioritise them for the time being.

The Double Diamond is so valuable for a founder because it helps them do one thing at a time, without racing ahead or second-guessing their research process.

It encourages you to think broadly, considering and combining lots of options.

It helps you focus on the problem in fine detail BEFORE jumping to solutions, which helps you design better products and services for your customers.

It helps eliminate 95% of your ideas, letting the strongest ones compete for the right to be the idea you take forward.

It helps you show your thought process, which is helpful for other team members, your board or investors.

Think of it like a bungee cord above a huge pile of crazy ideas – you get to dive in to the weird and wonderful possibilities, but it soon pulls you back out to reality where you can only do one thing at a time.

Co-Design

A founder can take all the right tools, lock themselves away from the world, and spend months designing a beautiful version of…the wrong thing.

That’s because the right tools still require the right people to be in the conversation – if we’re building something that people are supposed to use or enjoy, then we’d better understand what they want, what they hate, what they fear and how they naturally behave.

Imagine someone was trying to buy you a Christmas present, but didn’t want to meet you or ask you about things you’d like.

What are the chances of them buying you a gift you really appreciated?

If they don’t understand you, then the two most likely scenarios are that they get you a safe, generic gift, or they completely miss the mark.

Compare that to your friends pitching in for your Christmas gift.

They know you, they’ve listened to you, they know what you’ve already got and what you’ve been unable to justify buying for yourself.

They might not be able to read your mind, but they can also see things about you that you might not see yourself.

There’s a much higher chance that their gift is more delightful or more relevant, because they’ve put some thought into it.

If you thought of your business as someone giving a gift to your customers, which one would you rather be?

The complacent one, or the friend who puts in some thought?

This is why the field of co-design is so important.

A lot of good businesses have been created by founders who have “scratched their own itch” – they experienced a problem firsthand, were unsatisfied with the solutions that were available, so created their own solution.

Because they had a good understanding of themselves, their solutions were also a perfect fit for others in the same situation, giving them an audience of enthusiastic customers.

You’ll see this when you go to baby stores – shelves and shelves full of products designed by frustrated new parents, who were determined to scratch their own itch, making for a highly innovative and highly competitive market.

The trouble is, for the majority of new businesses, the founding team are not representative of their customers and end users.

That means they get to choose – do we want to put in the work to truly understand our market, or will we convince ourselves that we’re so smart that we already know what’s best for our market?

Co-design doesn’t require a new tool or template, it means involving your future customers and end users in each of the above stages of development.

For example, in the research phase, you might consider interviews with your target audience, to hear how they frame the problems they face and the ideas that excite them.

These conversations might also help you rank which problems are more pressing or most lucrative, versus the ones that are a “nice to have”.

In the prototyping stage, it might be wise to show and test these prototypes with the people you expect to use them, since their default behaviours, questions and suggestions are usually a huge source of insight.

If one user misunderstands what you’ve built, that’s their problem.

If every user misunderstands what you’ve built, that’s your problem.

In the validation stage, you might want to present your customers and users with an opt-in offer, to see if they’re actually enthusiastic about proceeding with what you’ve made.

If they say nice things, but don’t sign up or place a pre-order, then there’s something important that they don’t want to tell you.

Customer feedback is here for your benefit.

Yes, Henry Ford said that quote about people wanting faster horses, but that doesn’t mean you will always know better than your audience.

And if you do think you know better, then the least you can do is test your concepts with your market – let their enthusiasm turn into pre-orders.

Co-design can be as fast or as intensive as you want to make it – we’ve had projects where this was a few short conversations every month, and we’ve had projects where this was a series of long detailed workshops with complex data analysis.

The catch is, it’s really easy to get co-design wrong through unnecessary pressure, selective hearing and clumsy arrogance.

A short, cheap, humble process is better than a sophisticated, costly, overconfident process.

Embracing Uncertainty

The hardest part about the design process is that it offers so few guarantees, particularly around how long it will take.

This is directly opposed to the traditional forms of project management with deadlines, budgets, “announceable” updates and waterfall Gantt charts.

That’s because project management is about minimising uncertainty, whereas the design process embraces uncertainty.

You don’t know what you’re going to end up building.

You don’t know exactly who your customers and end users will be.

You don’t know what will delight or repulse your audience.

You don’t know which part of the problem has the most potential for improvement.

You don’t know what products and services will address the real issues.

You don’t know what features mean the most to your target market.

You don’t know if people will like it enough to pay for it.

You don’t know what new ideas or options might become possible in six months’ time.

And you don’t need to know.

You need to be curious, diligent, creative, empathetic, trusting in the right process rather than one single good idea.

“Certainty” blocks off new possibilities, and those new possibilities often hold the seeds of the next great new businesses.

At the very least, exploring your ideas with tests, prototypes and small bets reduces the risk and financial commitment you’ll have to make.

And with a 90% failure rate with the old ways, small bets might serve you very, very well.

The Design Process gives you a re-usable skillset, which will be handy for every project you work on in the future.

The templates are freely available and get easier with practice.

Customer interviews will become more natural.

Changing your mind feels less scary.

It costs so little, but it requires a genuine interest in people, their worlds, their aspirations and their problems.

And with no shortage of people and problems, we need more and more designers taking them seriously.