The Beauty And Drawbacks Of Design Thinking

Why do we like hearing about flaws?

It’s probably because most of us believe that nothing in life is perfect, and that anything that is trying to appear flawless is usually hiding something.

A flaw makes us comfortable, and more ready to believe praise.

This applies to advice too – be wary of people selling you ideas, systems and methodologies that are too good to be true.

Every entrepreneur will tell you that designing and building businesses is incredibly hard, so what are the chances that this “7-figure framework” will be as easy and guaranteed as claimed?

If a practitioner understands something, they should be able to present both sides – the pros and the cons.

The pros will hopefully outweigh the cons, but it’s helpful to know what to expect, and which parts will be the hard parts.

That brings us to Design Thinking – a mindset and methodology that attracts a lot of praise and case studies.

You’ve probably been encouraged to respect and celebrate design thinking, but actually applying it to your work is bound to meet resistance.

It’s a hard process to describe, let alone implement, and it goes against some of our base tendencies and default behaviours.

By naming those behaviours and uncomfortable tensions, you’ll see them for what they really are - signs that you’re doing the right thing, even when (and especially when) it’s difficult.

Lack Of Certainty

We once worked with a large business on some NDIS service innovations, over a six-month process.

It involved a lot of customer insights, customer interviews, business modelling and prototyping.

Towards the end, as we were presenting our ideas for testing and validation, they said to our colleagues “If these tests don’t work, will we get our money back?”.

You can see where they’re coming from – with every other problem they pay to solve, a service provider offers guarantees.

If your builder’s work falls apart, they’re obliged to fix it.

If the caterer doesn’t bring the food they promised, they’re not getting their payment.

Innovation is fundamentally different – it can’t be guaranteed or predicted.

You are committing to a process and a level of diligence, but who can realistically promise a certain deadline for success?

You can engineer a design process for the maximum chance of something working, but it’s probably not going to be revolutionary or unique.

Design Thinking is a process for reducing risk, making small bets and avoiding committing to ideas before they’re validated.

It can be conservative and cautious, it can be well-managed, but realistically it won’t come with a returns policy.

Lack Of Clarity

Innovation is generally interlinked with things that seem stupid.

Doing something innovative means doing things that have never been thought of, or that have not worked in the past, or have been deemed impossible and never attempted.

That means innovation will be full of surprises, both at things that don’t work but should, and at the things that shouldn’t work but do.

At a practical level, that means your work is probably going to feel pretty miserable or unclear right up until you have your breakthrough.

It will make it hard to plan out GANTT charts and waterfall diagrams, because we don’t know when we’ll be pivoting, re-running steps or accelerating.

The process won’t come with a map, it comes with a flow chart, one with arrows that sometimes go backwards or send you down an unappealing path.

But then, when you’re busy finding your way around, why would you want a map of a different city?

Cheating

Though they rarely admit it, a lot of entrepreneurial leaders and executives have a strong desire to look smart, save time, save costs and reach a conclusion quickly.

They feel like there’s a spotlight on them, with a ticking clock and high expectations from their teams or funders.

They’re asked to make promises and guarantees, which as we’ve just seen aren’t really theirs to make.

Steve Blank said “Cheating on your discovery interviews is like cheating on your parachute packing class.”

It’s a brilliant analogy, because it reminds us that the point of these exercises is to keep us safe.

It’s not an exam with an assessor, it’s our chance to see if we’re happy committing a lot of our time and money pursuing a particular opportunity.

Cheating gets you nowhere because the only ones truly judging you are customers, who vote with their feet and their wallet

And when it’s your parachute you’re packing, you have extra reason to do a damn good job.

Customer Centricity

Mark Ritson said “The first rule of marketing is that you are not the market”.

And Charles Eames said "The role of a designer is that of a good, thoughtful host anticipating the needs of his guests".

These two quotes remind us that we are building solutions and offers for someone else, with different needs, biases and preferences than our own.

Like a good host, you might have good insights into what people enjoy, and that allows you to make them as comfortable and engaged as possible.

But customer centricity is hard because it’s uncomfortable walking in other people’s shoes.

We’re bound to make incorrect assumptions, and even tell ourselves that the customer is wrong (and maybe in a way, they are), but most customers are looking to be served, not educated.

It’s hard to take someone else’s perspective, but it gives you the best chance of creating something they can use, enjoy, and recommend to other people.

Rapid Movement

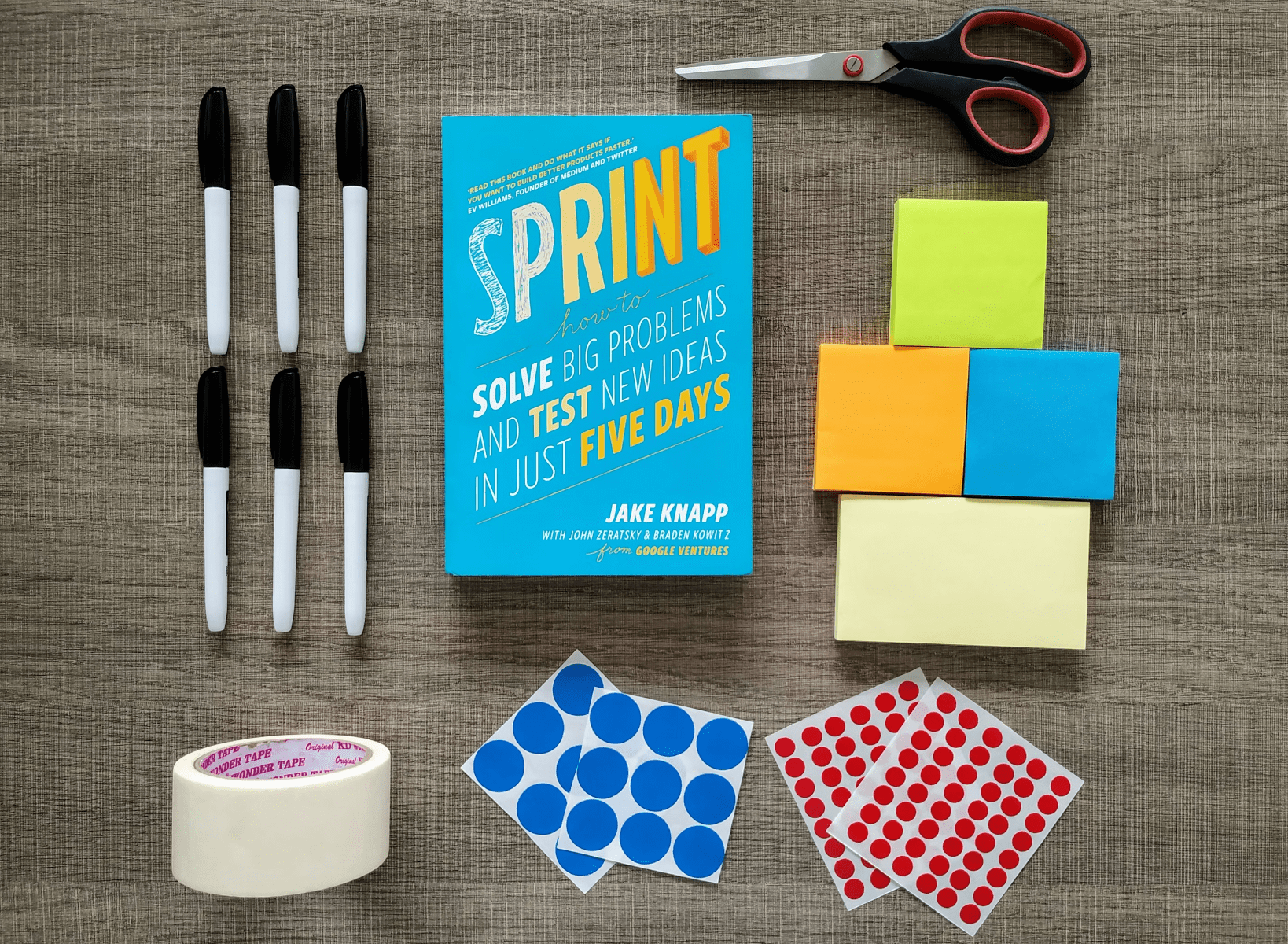

The design process often involves a series of “sprints”, which are a fine thing to agree to in a planning meeting.

Sprints are hard!

They’re hard because they involve tight timeframes and a sense of urgency, but also because you’re running towards the difficulty.

The difficult tasks are hard because they often involve creating something out of nothing, trying things that might flop, talking to customers who might not encourage you, and generally involve emotional labour.

Rapid movement does not mean skipping steps or jumping to conclusions.

In fact, there’s a valuable skill to be learned around entrepreneurial shortcuts – which things can be sped up and which things need time to develop.

Generally speaking, people who try to take two shortcuts in a row are red flags.

One shortcut can be wise, but layering shortcuts back to back usually means the entrepreneur isn’t truly listening for feedback from their market, and isn’t getting the benefit of the work.

Rapid movement is one of the only areas in which a startup has an advantage over bigger competitors.

It isn’t easy for the solo founder or startup team, but it’s almost impossible to work quickly within a large corporation or government department.

Startups don’t have to be conservative because they have nothing to conserve, and that makes their larger rivals nervous.

“Aha! Moments”

Good companies, products and services are often built on top of an elegant insight or “Aha! Moment”.

Some of these become a part of startup mythology.

e.g. Ingvar Kamprad detaching the legs of his table to better fit it into a moving truck, or the founders of Airbnb renting out their inflatable bed in San Francisco.

These moments can provide clarity, inspiration and a vision for a good business.

They are also hard to predict, hard to schedule, and often involve a pivot.

Aha! Moments usually happen in close proximity to your customers, or when you’re making prototypes, or when you’re learning from what other businesses are doing in parallel industries.

You can boost your chances of them occurring, but you can’t schedule them into your team calendar.

Pivots, Experiments and Sunk Costs

In the early days of The Difference Incubator, I would lament something that seemed to happen with great regularity.

One or both of our co-founders would come back from a lunch meeting or walk, full of excitement and news.

This news generally sounded like “Scrap what you’re doing, here’s what we should do instead”.

I would take a big inhale, breathe it out slowly, and say “Ok, what do you need me to do?”.

Now to be clear, the design process is full of these sudden changes, and I did the right thing by rolling with the changes.

But it was always a bad feeling, and I was always rattled, and it took a little bit to feel good about discarding what I’d put work into.

It is easy to feel like you’ve wasted past efforts, but I needed to learn that experimenting and prototyping are good uses of time even if they fail or become obsolete.

You’ll need to become comfortable with embracing or accepting sunk costs – changing or shelving something that you’ve put labour and money into.

By pursuing several paths or solutions, we’re guaranteed to bin some or all of them, so we might as well accept that our work won’t have earned permanence.

Mixing and Matching Recipes

Startups can learn a tremendous deal from those who have come before them, but often in little pieces.

That’s because the business and design worlds have timeless principles not timeless recipes.

Heraclitus said “A man cannot step into the same river twice, because it is not the same river, and he is not the same man.”

Your circumstances are different to the inventors of the past: your market is different, your tools are different, your competitors are different, your whole industry is different.

You won’t be able to wholly copy someone else’s work, but you can combine elements of several distant concepts, models and features.

This is a big opportunity for tech enabled businesses, who are combining strengths of several existing products and services.

e.g. mimicking Tinder’s “swipe right” on apps, integrating well designed payment gateways and user interfaces, applying certain design styles that have worked for brands you find elegant or engaging, using pricing strategies that give customers flexibility or a helpful nudge.

You don’t need to invent everything from scratch, innovation can come through combinations and repurposing of existing concepts.

Doing that mixing and matching can be hard, because it involves trial and error and a lot of thought experiments.

Two good ideas might be a terrible fit, and two random ideas might become a beautiful combination.

Models Have Expiration Dates

Your seven-year financial forecasts are a fantasy.

They are fan-fiction, an idealised picture of the future that is guaranteed to miss the mark.

What businesses are assured of relevance and competitive strength seven years from now?

How well could a company have predicted what this year would be like seven years ago?

The truth is, no one is guaranteed permanence in the market, but every company assumes that disruption won’t happen to them.

Business models have expiration dates, and they can sneak up on you.

Avoiding disruption usually comes from proactively disrupting yourself – building and becoming the company that would put you out of business.

It’s hard, it’s uncertain, it has a cost to it, but better you than your rivals.

Which brings us to the other side – your competitors’ models have expiration dates as well.

We naturally assume that those who are currently strong will be strong forever, and yet in every decade we see that to not be the case.

What might replace and supercede your competitor’s model?

Can you design and test some options faster than them?

Tradeoffs

Tradeoffs are the essence of strategy – deciding what NOT to do is as important as deciding on what you’d like to be known for.

You can’t please everybody, you can’t be a master at everything, you can’t be both the best and the cheapest in your field.

If you don’t agree, simply name the businesses that are currently doing it?

And yet, passionate leaders and executives hate this idea, and think that they can use their work ethic to be all things to all people.

But there’s a positive – the opposite of a good idea can also be a good idea.

If your competitors have made a particular tradeoff choice, you can pursue the opposing strategy and still find success.

There is room in your industry, room for specialists and generalists, cheap-and-cheerful and prohibitively expensive, socially conscious and egotistical, limited range and customised.

You can pretend these tradeoffs don’t exist, or you can embrace them.

At the very least, you can test these options and let the market show you what they like.

Writing Your Principles In Pen

They say you should “write your principles in pen and your business model in pencil”.

Nobody gets to change your mind about what you care about, but you can’t tell the market how to behave.

You’re going to have to constantly revisit those principles and beliefs, and constantly adjust your business model and plans for the future.

That might be frustrating to hear, but it’s also a relief, giving you permission to stick to your guns and your values, in exchange for flexibility on what makes your ideas desirable, feasible and viable.

Design Thinking and the broader Lean Methodologies are genuinely helpful and will make your work stronger, but the work is still hard.

It forces you to front-load the hard parts, it pushes your ego to the side, and it disregards your idealised timelines and business plans.

And even with their challenges, they’re still better than the old ways of starting a business.

9/10, would definitely recommend.