Technical Problems and Adaptive Challenges

People often talk about entrepreneurs being problem solvers, but there are two different types of problems, and they’re easy to mix up.

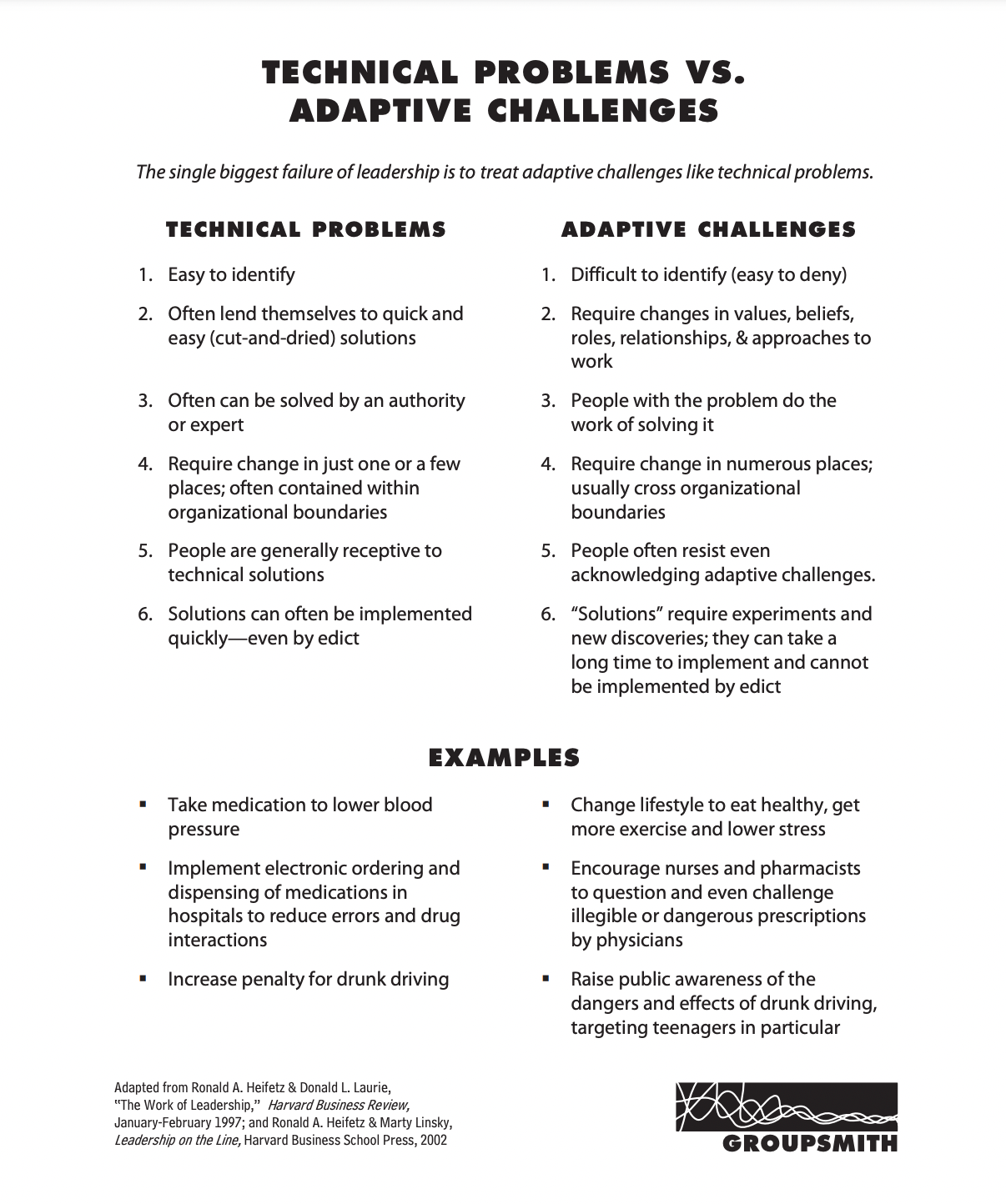

Ronald Heifetz describes them as Technical Problems vs Adaptive Challenges, and offers some guidance on which is which.

Here’s the famous worksheet:

Technical Problems are:

Easy to identify

Often lend themselves to quick and clear solutions

Often can be solved by an authority or expert

People are usually open to technical solutions

Technical solutions can often be implemented quickly—even if it’s forced upon you by an authority figure

Adaptive Challenges are:

Difficult to identify and easy to deny

Require changes in values, beliefs, roles, relationships, and approaches to how to accomplish goals

Require some root-cause analysis

People with the problem are the main actors who need to do the work of solving it

Require change in several places; usually cross organizational boundaries

People often resist even acknowledging the issue.

Solutions require experiments and new discoveries; they can take a long time to implement and cannot be implemented by force

For example, if the office printer is jammed or out of toner, we have a technical problem.

Until the jam is cleared or we’ve swapped in a new toner cartridge, there’s no more printing.

No complaining or arguing is going to help, it’s stuck until it’s resolved.

On the other hand, becoming a paperless office is an adaptive challenge, requiring a broader level of behaviour change from the whole team.

We can’t make every change instantly, and it’ll require some creative thinking to work out how to avoid falling back into old habits.

When we need to send a document and the printer is offline, someone saying “we shouldn’t even be printing in the first place” is unhelpful.

Vice versa, going paperless can’t be achieved with a big purchase or an announcement – it will take the buy-in and participation of everyone, and can easily be stalled or undermined.

That leads us to Ronald Heifetz’s main point:

“The most common leadership failure stems from trying to apply technical solutions to adaptive challenges.”

Technical solutions are so enticing for leaders and entrepreneurs because they are able to be project managed.

You can make a decision to bring in the best solution, draw up timelines and budgets, and go to knowledgeable people who have done this before.

And none of that works for adaptive challenges.

More Examples

Once you understand the difference between the two, you’ll see examples everywhere.

Having your phone run out of battery is a technical problem, which can be solved by a powerbank.

Halving your daily screen time however, is much harder to resolve, involving new habits, routines and using your willpower.

Some diseases have been eradicated through new medicines, like Polio and Smallpox. These have been technical solutions that are rolled out through co-ordinated campaigns.

By contrast, Ignaz Semmelweis, discovered the power of antiseptics for hospitals, through innovations like hand washing before surgery. Even after making his breakthrough discoveries around germs and infection, his work was dismissed and ridiculed by most other surgeons at the time – a horrible adaptive challenge.

Conversation around the gender pay gap usually breaks down when people deny its existence, pointing out that their company has one pay scale that applies to all employees.

This fails to consider all of the deeper systemic issues, none of which look like overt sexism, but result in a significant difference in earnings potential and career advancement.

You can bet that this won’t be resolved as long as there’s denial over the existence of the problem.

Some of the challenges around working from home have technical solutions, such as Zoom, Slack, and standing desks to prevent fatigue.

These were figured out pretty quickly and have been widely adopted.

Today, employers are having a terrible time adapting to this newer way of working; how it changes productivity metrics, team culture and remuneration.

Once employees reluctantly adapted to a new way of working, it’s been tricky to entice them back into old patterns and workplace norms.

Apple’s decision to remove the headphone jack from the iPhone was widely disliked. Apple offered a flimsy $15 adapter for the 3.5mm connector, and anyone who used one will know how awfully they performed as a technical solution.

Instead, Apple trusted that the market would begrudgingly adapt to Bluetooth headphones, and sure enough, they did.

This was assisted by the rise of AirPods, which managed to solve many of the issues facing previous Bluetooth earbuds.

Electric cars face both types of problem.

There’s the technical problem of the battery and the amount of charging stations available in different parts of your country.

There’s the adaptive challenge of “range anxiety”, in which owners worry about making it to the next charging point in time.

There’s the adaptive challenge for governments to accommodate or incentivise these vehicles too – Australia had a short-lived tax on EVs, and the US has to re-think their dealership policies that make it hard for new companies to sell their cars directly to customers.

This Week In Australia’s Parliament

We recently saw a video from an Australian Senator, Jordon Steele-John, in an debate over how Parliament House continues to be inaccessible and unaccommodating to people with disabilities.

What becomes clear is that the two are talking at odds; one is trying to describe the situation as a technical problem (issues with replacing loud clocks), whereas the other is incredulous that accessibility is not being taken seriously as an adaptive challenge.

You can bet that if Parliament’s clocks stopped working, there would be an immediate fix rolled out within days, but accommodating neurodivergent workers does not seem to carry the same urgency.

Whatever your opinion on the clip, it’s a good example of how the two framings of a problem lead to mutual frustration.

How This Affects The Entrepreneur

Entrepreneurs go looking for problems and then create businesses that can (profitably) solve them.

Our business brains tend to gravitate towards technical solutions – products and services that we can conceptualise, name and market to an audience.

That creates a bias towards ideas that are easy to imagine, and ignores how murky adaptive challenges can be.

Adaptive challenges are about behaviour change, something that a lot of customers tend to resist, and require either a substantial incentive or threat in order to form new habits.

For example, AI is a hot topic online and in the media, but less so in a lot of workplaces.

These technical solutions are evolving at a rapid pace, whereas business owners and managers seem slow to understand, let alone embrace, how AI might benefit their organisation.

It’s not enough to prove what AI can do, it’s about making people feel comfortable with trusting AI to do a certain calibre of job with a certain level of reliability.

Then there are fields where we are waiting for technology to catch up – arguably including cryptocurrencies, virtual reality or autonomous cars.

You cannot persuade or support a customer into using these technologies in a seamless way, the solutions are not yet useable for the majority of the population.

That will likely change, probably faster than we anticipate, at which point new household names will emerge as leaders in these fields.

This will come in to your customer interviews – understanding whether your customer sees their situation as a “vitamin, painkiller or oxygen” level problem.

Solutions come with a cost, and it can be culturally awkward to say that the cost is too high.

Business owners and customers are constantly deciding that the cost of change is too high, but often in subtle and unspoken ways.

If the problem is severe, a customer will have looked for a solution already.

They might not have found one, due to a lack of good technical options or not having a clear sense of how they might change their behaviour, but if they haven’t bothered to look, then this isn’t a big deal in their world.

The entrepreneur’s job is not to persuade them or coerce them, we can only meet them where they are and speak to them in their own language.

If they’re denying a problem exists, they aren’t going to be your early adopter.

An entrepreneur should start by asking the big question: what sort of problem am I dealing with?

Is this a technical problem, which will require a technical solution?

Or is this an adaptive challenge, which will involve systems design, persuasion, incentives and patience?

You can’t change your mind out of a technical problem, and you can’t buy your way out of an adaptive challenge.