Impact Models And Your Recipe For Change

Any entrepreneur who wants to create change is designing an impact model, whether they know it or not.

This describes what your business does, what that work leads to and what long-term ripple effects will be felt in the future.

If we start taking action without any foresight or plan, we usually end up with unintended consequences, and these aren’t always good.

The social enterprise graveyard is full of well-meaning organisations whose unintended consequences far outweighed the good they were able to do.

We need a plan for what resources we need, what we’ll do, what we’ll create and how we’ll know the work is effective.

Once we’ve found a way of creating that change, we’ll probably want to keep doing it.

Your plan becomes a recipe; it describes a repeatable process, broken down into simple steps with clear instructions so that you consistently achieve what you aimed for.

If someone takes the same ingredients, does the same actions, they can reliably expect to create the same results.

Let’s look at your impact model and begin drafting your recipe for change…

Describing What You Want

To understand all of your choices, we first need to understand you.

We need to understand what you care about, where things are today and where you’d like them to go in the future.

You get to choose the topic, cause or focus area of your work.

Usually this is something that is close to your heart and is “due” for change.

You might try some prompt questions like;

· What are my friends sick of me talking about?

· What makes me angry?

· I can’t believe it’s 2023 and we still…

· What are the root causes of these big problems?

It’s easy to mix up Vision and Mission, which are connected but different.

A vision describes the finish line – the better world that you want to bring about.

A mission describes the action you want to take in order to bring about that better world.

We find these prompts are helpful:

1. We believe in a world where…

2. But the reality today is…

3. So we will…

That first prompt creates a version of your vision, the second prompt creates a description of the current context, the third prompt creates a version of your mission.

You might find that a lot of people share your vision, but have a different approach to their mission.

Options For Your Mission

For example, you and another changemaker might share the vision of “We believe in a world where women make up 50% of the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) field”, but have very different “So we will…” plans for what to build.

That’s a good thing, we want lots of people each making contributions to the “better world” we dream about, and that’s going to take lots of different initiatives.

For the Women In STEM example, these missions might include:

· So we will create specialist training programs for girls in high school

· So we will run a specialist careers counselling service

· So we will create a platform promoting examples of women in STEM

· So we will start an agency that exclusively hires women for STEM roles

· So we will start an online school in the Metaverse teaching STEM subjects

It would be incredibly difficult to try and do all of the above at once.

Strategy is about tradeoffs, and you’ll need to start with a realistic mission before thinking about expansion and replication.

What you often find is that there are other people working on the same sorts of things as you, and it’s usually better to see them as allies rather than competitors.

You can share insights, form partnerships and learn from each other’s mistakes.

Eight Word Mission Statements

Kevin Starr argues that a good Mission Statement should be able to be summarised in eight words, and includes “A verb, a target population, and an outcome that implies something to measure”.

Some examples include:

“Restore coral reefs in Papua New Guinea”

“Double the incomes of farmers in Northern India”

“Remove single use plastics from Australian supermarkets”

Eight words is deliberately limiting, but those limits force you to get straight to the point – no fluffy language or aims that can’t be verified.

We need something measurable, or else how will we know that change is happening?

Finally, it can help to ask yourself these three questions:

1. Why this?

2. Why me?

3. Why now?

To paraphrase one of our favourite quotes: Write your cause in pen, and your impact model in pencil.

You own your cause, but your recipe for change should be up for discussion.

Drafting Your Recipe

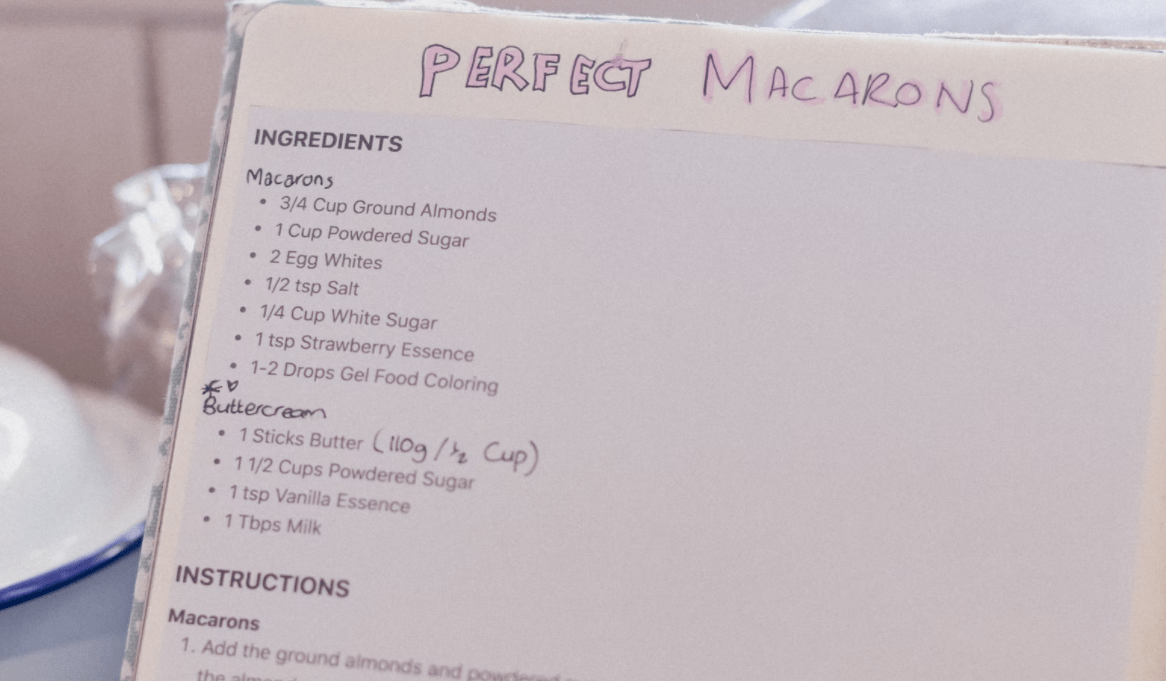

“A recipe becomes yours when you write it out in your own words, threading it with details that reflect your personal experience with it and your conviction that what you're presenting are all the right ingredients, as well as the best way to combine them.”

– Merrill Stubbs, Food52

Once we understand the overarching mission, we then need to create a repeatable recipe for how we’ll make it a reality.

There are usually several ways of achieving an outcome, and we want to find one that genuinely works before trying to scale it more broadly.

If a solution works once, but only because of a lot of good fortune, good funding or circumstances that won’t come around again, it was a good project but probably not a good recipe or impact model.

If we pick a mission like “Double the incomes of farmers in Northern India”, we could look at options like donations, fundraising, improved agricultural inputs, improved education, improved infrastructure, better market access, etc.

All of these can work, but some are far harder, far costlier or more temporary than others.

To use the old expression, donations are “giving a man a fish”, whereas improved agricultural inputs and better market access would be “teaching a man to fish”.

Inputs, Activities, Outputs and Outcomes

Recipes are an excellent analogy for an impact model – they describe the ingredients/inputs we use, the activities and steps we go through, the immediate outputs we end up with, and the long term consequences and effects of the work.

You might have used a recipe like this:

Inputs – Flour, eggs, sugar, butter, cocoa, icing sugar, sprinkles, candles

Activities – Mix, bake, cool, ice, decorate, set alight, sing a song

Outputs – A birthday cake, a good photo opportunity, a messy kitchen

Outcomes – Delight my guests, delight the birthday person, feed everyone, create lasting memories

You control the inputs and the activities.

You end up with a set of results and outputs.

You cross your fingers and hope that these lead to your desired Outcomes.

If they don’t, then the inputs and activities might need to change.

Constraints and Modifications To The Recipe

That birthday cake recipe is pretty clear – someone on the other side of the country could follow the steps and reasonably expect to get a similar result.

But it’s not universal and it’s not bulletproof; we might need to adapt the recipe in order to maintain the target outcomes in different circumstances:

· The birthday person doesn’t like cake

· Guests have food allergies

· We won’t be near a kitchen

· People are on controlled diets

· We have limited funds

By understanding the constraints, we can modify the recipe to reach the same outcome; a happy birthday person and a well-fed crowd.

· We could substitute some ingredients; using gluten free flour, egg substitutes, natural sweeteners, etc.

· We could choose a different type of dessert; making a gingerbread house, an ice cream cake, crème brulee, fruit salad, etc.

· We could buy some pre-made components; baking in advance, buying a cake to decorate, using a packet mix, etc.

This forces us to revisit our initial recipe ideas and understand why they work, so that we can keep them working when circumstances change.

· Does it need to be a cake?

· Does it need to be sweet?

· Does it need to be food?

· Does it need to accommodate literally everyone, or can we make two solutions?

That helps us know what substitutions and modifications will work, and which ones will rip the soul out of the initial idea.

Recipes For Social Impact

While you might not be making birthday cakes, your mission has similar complexities.

· Who is it for?

· What constraints do we have?

· What resources and assets do we have?

· Do we want to serve a few people with a lot, or a lot of people with a little bit?

· Can we articulate how to start from scratch?

· Can we describe how we make intuitive decisions?

If you have a good understanding of your mission and your context, you’ll be able to choose the right recipe for the job.

You can explore several options and compare them before making a commitment, giving each one the best chance of success.

For the Women In STEM example, we were considering:

· Specialist training programs for girls in high school

· Specialist careers counselling services

· A platform promoting examples of women in STEM

· An agency that exclusively hires women for STEM roles

· An online school in the Metaverse teaching STEM subjects

These are not inherently “good” or “bad”, but it’s likely that some are more suited or less suited for your audience and your context.

Case Study – Underage Drinking

Teenage drinking is an issue in a lot of countries, and one that concerns a lot of people.

A lot of recipes have been tried, to mixed success:

· Adjusting the legal drinking age: “if we delay them until they’re older, they’ll make better choices”

· Making alcohol harder to acquire: “if alcohol can only be purchased ahead of time, we reduce the chances of teenagers opportunistically extending a session into a binge”

· Making alcohol more expensive: “if alcohol is more expensive, they won’t be able to afford 10+ drinks in a night”

· High penalties for venues serving intoxicated/underage drinkers: “if we threaten the servers, they won’t want to risk supplying underage people with alcohol and will help us uphold the law”

· Health campaigns in schools: “if we explain the dangers of alcohol and show people what constitutes a standard drink, we can discourage them from making poor choices (or at least help them accurately measure their alcohol intake)”

· Heavy penalties for teenage drink drivers: “if we make drink driving extremely costly, we encourage designated drivers and therefore reduce the risks for their friends and the broader community”

· Encouraging parents to model healthy behaviours and attitudes towards alcohol: “if they try alcohol in moderation with us at home, they won’t try silly things with their friends in a park”

· Complete cultural prohibition of alcohol: “if we outlaw alcohol, all of its evils go away”

Some of these recipes have worked, to some extent, some of the time.

Your country might have used some approaches and not others, and you can form your own conclusions about whether they work.

In each case, there’s an intervention, and an assumption of what that will lead to.

But these assumptions assume that teenagers can be predicted or influenced by rules or policies.

Teenagers are clever and, when motivated, have found ways around all of these approaches.

But that doesn’t mean they are “bad” recipes, or that we should stop those approaches.

It might mean that we still need new recipes, with new thinking for a new generation.

The Friendship Bench

Case Study – The Friendship Bench

Dr Dixon Chibanda is one of the few psychiatrists in Zimbabwe, who saw first-hand the devastating effects of depression and suicide across the country.

Zimbabwe has many challenges, formal psychiatric support is nearly impossible to access, and there is a social stigma that often prevents people talking about what they’re going through.

Dr Chibanda’s clever solution came from seeing two groups of people who were each feeling lost, but who could help each other:

· Young people with anxiety and depression, experiencing “kufungisisa”, or “thinking too much” in the local language, who could use someone to talk to.

· “Grandmothers”, volunteers from the community who have been trained in cognitive behavioural therapy, and who are looking for meaningful things to do.

So Dr Chibanda prototyped and refined his innovation: The Friendship Bench.

It’s a wooden bench outside of health care centres, where people can talk to a grandmother for six 45-minute sessions about what they’re going through and what they can do about it.

After those six sessions, participants are invited to a peer-led group called “Circle Kubatana Tose”, meaning “holding hands together”, where they are introduced to other Friendship Bench participants, which helps people discuss and solve their own problems.

The results have been phenomenal – studies showing an 60% improvement in quality of life for participants, and a five-fold reduction in suicidal tendencies.

Over 1,400 community workers have been trained in this “evidence-based talk therapy”, supporting over 150,000 participants.

The recipe is important – we don’t want to pretend that park benches prevent suicides.

The magic is in the inputs and activities, in recruiting the grandmas and training them in locally designed therapeutic techniques.

Dr Chibanda has been intentional in having the program scrutinised and evaluated, to verify that it works and to demonstrate the change it creates.

It’s a deliberate design, made elegantly simple through research and refinement.

We could speculate that the recipe might look something like:

Inputs – people struggling with their mental heath, grandmothers/volunteers from the community, specialist trainers, wooden benches

Activities – tailoring evidence-based therapy techniques for the Zimbabwean context, training grandmothers in cognitive based therapy, advertising the offer, holding six 45-minute sessions per person, an extension offer of six peer-led sessions as a follow up

Outputs – participants feel heard, understood, equipped and supported; grandmothers feel valued for their contributions

Outcomes – increased quality of life and decreased rates of suicide for participants, meaningful work for grandmothers

This unlikely recipe is working well, and is now being rolled out in different cultures and contexts.

Good Intentions And The Helicopter Test

We once worked with a consultant on an impact evaluation project who used a great hypothetical question:

“Whenever I’m assessing the benefits of a program in the developing world, I ask myself; would people be better off if we’d have gone up in a helicopter, taken this money and scattered it above the town?”

It’s a showstopping question, and in that specific case we all knew the answer – the project we were assessing would have been much better off throwing their $300,000 budget out of the helicopter.

That’s damning of the organisation’s recipe for change.

If our recipe doesn’t create something better than the most basic alternative, what are we doing?That would suggest the ingredients, funds and resources would be better spent going directly to your beneficiaries, or at least to your competitors.

Behaviour Change

While the inputs/ingredients and activities/steps are within your control, they are all designed to change someone’s behaviour.

If there’s no behaviour change, there’s no positive outcomes or impacts.

Anyone working on an impact project needs to consider four questions:

· Whose behaviour needs to change?

· What do we want them to do?

· What do we want them to stop doing?

· Who else should change?

Case Study – Keep Cup

Keep Cup is an Australian company that designs and sells stylish reusable cups – some made of plastic, some made of glass.

Keep Cup’s behaviour change recipe can be summarised as:

1. Create stylish and aesthetically pleasing reusable cups

2. Work with baristas and café owners to make them easy for cafes to accept, or even sell to customers

3. Customers buy and carry their cups with them each day

4. Customers use their Keep Cup instead of a takeaway cup

5. Customers continue this habit for months

In this example, we can spot three important behaviour changes:

· Cafes promote and accept customers bringing in their own cups, which was previously unthinkable

· Customers choose a cup they like and use with pride

· Customers keep up this habit at least twenty times, in order for the cup to environmentally “break even”

If the cafes reject the cups, customers stop trying.

If customers don’t like drinking from the Keep Cups, they’ll stick with the takeaway cups.

If customers hide their Keep Cups in their shelves to gather dust, no good outcomes can happen.

During COVID lockdowns, customers of our nearby café could be seen buying takeaway coffee in a single-use cup, and pouring it into their glass Keep Cup.

It was the hygienic thing to do, but it didn’t help the environment – the takeaway cup still ends up in landfill.

You’ll also see large companies and institutions create their own branded Keep Cups to give away as gifts, and in the majority of cases they pick an ugly design.

If the recipients are too embarrassed to carry these cups around, then the whole process has probably created a net negative result.

The genius move that Keep Cup made was in their design of the cups and in winning over café owners/baristas.

Those are the two main elements the business can control, and they are designed to give the best chance of a customer using their Keep Cup again tomorrow.

It’s part of why they introduced a glass version of the Keep Cup – it’s not as good for the environment and they’re less durable, but it enticed more and more coffee snobs to switch to a reusable cup each day.

For your work, you get to think about the same things:

· What is our desired behaviour change?

· How might we nudge people towards these better behaviours?

· How will we know that they’re changing their behaviour?

· Is there a chance we’re accidentally making things worse?

Validating Your Recipe

Thought experiments are helpful, but there’s a different level of clarity you get from actually trying the recipe – firstly on your own, then in conjunction with someone else, then without you being there.

That’s the true test of a recipe; does it work for someone who hasn’t tried it before and who doesn’t have your experience or intuition?

By trying it yourself, you get a first-hand look at what you create, what it leads to and how it ends up.

By working with someone else, you hear what questions they ask or suggestions they make, and can see which steps confuse or excite them.

By giving the recipe to someone else, you can see how they interpret each stage, take shortcuts or make errors, which might lead you to a valuable insight.

There are several benefits from these tests:

Variation – seeing how others adapt this recipe to their context and preferences, for better or worse.

These reveal which parts of your recipe are integral to its success, and which elements are easily adjusted to suit a new audience or circumstance.

Simplification – finding ways of shortcutting processes, avoiding extra work or using more readily available inputs.

Like in cooking, some things are easy to substitute and some aren’t, and you usually discover these the hard way.

Miscommunication – one of the most painful parts in watching someone else follow your instructions is when you see them misinterpret a vital step.

In most cases, this is your responsibility to address, by changing how you explain the work.

It might be that you need a diagram, a rule of thumb, an analogy or a short video, all of which highlight what a good outcome looks like and what a bad outcome looks like.

It also might show you that there are additional prerequisites someone needs if they’re going to do a good job of following the recipe.

Case Study – WeWork in Melbourne

A great example of a recipe in need of variation is WeWork.

Their recipe was perfect for cities like New York in 2008:

· Gather motivated freelancers and creative entrepreneurs

· Host them in cool coworking spaces

· Run some events

· Sparks fly and new connections are formed

· Talk about stories from these new collaborations

WeWork’s founder described themselves as a technology company, who were able to make one plus one equal three, and for a short time they put forward a compelling case.

But the recipe doesn’t translate into a city like Melbourne, Australia.

Melbourne’s startup community is different – it’s vibrant, but not extroverted.

You can’t just put everyone in a room and expect magic to happen, we need more facilitation and context to form relationships.

A skilled networker can make that happen, but WeWork’s Melbourne team were basically reception staff and facilities managers.

Coworking is different too, most of the WeWork offices in Melbourne were taken up by mid-sized companies who were downsizing, and wanted to save on costs.

They appreciated the communal facilities, but weren’t there to make friends or new connections.

Once they got a taste for coworking, and saw that WeWork’s recipe wasn’t special, they mostly moved to cheaper spaces, and didn’t look back.

With a building full of introverts and a local staff who’d never seen a vibrant WeWork community, there hasn’t been many success stories to talk about.

In hindsight, the original WeWork recipe did work, but in rapidly scaling it across the world, it lost its essence and became a serviced office.

A good coworking space can be a good business, but they might choose not to make inflated promises that set customers up for disappointment.

Objections To Testing

These tests are a crucial step of the design process, and yet people often resent them.

These objections usually come down to two bad traits:

Cowardice – the fear that the tests will expose issues and undermine your credibility.

Arrogance – the belief that no improvement is necessary, and that success is inevitable.

Neither of these serve you well in the long run.

Testing your impact model is similar to testing your business model, and the same prototyping tools are useful.

These experiments are less daunting when you treat them like small bets, never risking too much money or energy on any one experiment, and trialling several variations to see where there’s the biggest payoff.

It's also helpful to try your first tests in secret, without an audience and without expectations, so that you’re not worried about a failed test making you look bad.

Failed tests are valuable and serve you well, but you might choose not to talk about them until you’ve got a recipe that is consistently producing good results.

Measurement And Attribution

While your impact model can observe long-lasting effects that stem from your work, you’ll need to decide what is and isn’t your responsibility.

The comedian and talk show host Seth Meyers believes that he was the reason why Donald Trump won the 2016 US Presidential Election, stemming from an insult at the 2011 White House Correspondents Dinner:

“Donald Trump has been saying he will run for president as a Republican, which is surprising since I just assumed he was running as a joke.”

That insult, it turns out, has been identified by some as the moment when Trump decided to take his campaign for President seriously:

“I made fun of him in 2011. That’s the night he decided to run,” Meyers said. “I kicked the hornet’s nest, you just rubbed the hornet’s head. It’s not the outcome I wanted, but that’s history. I got a man elected president. I want my points.”

While Seth Meyers might see the funny side, the original writer of the insult was Jon Rineman, who is haunted by his impact:

“I’ve been in therapy over this,” says Rineman. “Of all the jokes I wrote in my life, that one took zero thought and effort, and there was no malicious intent. But we all know what happened after that.”

Irrespective of your views on Trump, these sorts of stories are fascinating, because they show us in hindsight all of the butterfly effects, hidden connections and unexpected ramifications of what we do every day.

You can see the dots that link Jon Rineman to Seth Meyers, Meyers to Trump, Trump to his campaign team, to the Republican Party and eventually the White House.

But is it fair for the comedians to genuinely blame themselves for whatever Trump did in power?

Probably not, and that’s why assigning attribution is so important.

There are so many steps and pivotal moments in the lead up to every presidency.

It’s not reasonable to tell every joke writer that they hold the fate of the country in their notebooks.

Entrepreneurs get to decide where they want to take attribution for a result, but they then own the consequences, good and bad.

This requires the entrepreneur to take some sort of measurement at the same point, so that they’re clear on what has changed and by how much.

Let’s say you’re creating a program for high school students in an underserved community. You might measure the number of students who started the program, the number who graduated, and the number who were offered a place at a university.

There is a temptation to report on how many accepted their offer to a university, but that decision might be out of your control, or they might have declined the offer for a very good reason.

Peter Drucker said “What gets measured gets managed”, and metrics tend to become targets.

This is why fitness trackers lead to increased outputs – if you track your steps, you’ll start finding ways of taking more steps.

While that might be a good thing for your fitness, it can backfire with your impact model.

Goodhart’s Law says “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure”.

So if your education program becomes fixated on the percentage of students who finish the program, the temptation is to change your behaviour to improve that statistic.

And while the intent of your program was to be inclusive and supportive, you’re gradually tempted to only accept students with a high likelihood of completion, or will make it harder for students to leave.

Over time, this pushes you further and further into decisions that look great on your annual report, but go against the original intent of the work.

Your job is to decide what you want to measure, and then clearly state which outputs or outcomes can reasonably be attributed to you.

Remember it’s a double-edged sword, and you probably want to take credit for results where you’d also accept blame.

Improving Your Recipe

Impact models, like recipes, change over time.

In the same way that some 1970’s recipes seem unappetising or obsolete (especially those involving gelatine or boiled vegetables), so are the old ways of trying to help.

Thirty years ago, well-meaning young people in Australia would raise funds to fly to a developing country, so that they could help build new houses or orphanages.

Their hearts might have been in the right place, but in hindsight, do you think the local residents would have preferred the amateur labour of a Westener, or rather have them send over the money they raised?

Did we really think there were no local builders?

Was a building the missing piece for these enormous systemic issues?

It was a nice idea, but in terms of dollars versus outcomes, it was an underwhelming recipe.

The same goes for microfinance – heralded as a fantastic social innovation in the early 2000’s, and now being re-evaluated in light of the results and alternatives.

It’s likely that our current approaches will look equally naïve in the future, and that’s a sign of good progress.

One of the most interesting pieces of self-analysis in the past few years was Thank You’s Letter From The Trustees, in which they outline why their old recipe wasn’t working well enough, what changes they were making, and what improved behaviours/outcomes they hoped to see in the future.

The social enterprise ecosystem had long been skeptical of Thank You, and this open letter was a fascinating agreement to that legitimate criticism.

Good chefs learn from other good chefs, and so while you’re tinkering and experimenting with your recipe for impact, there’s a lot of benefit in learning from your peers around the world.

This is why it’s so important to be engaged in a community of practice, to see how other groups are finding success and learning where your model might be backfiring.

You don’t need to automatically accept all criticism or rush to new trends, but use it as a prompt to test their suggestions for yourself, and see if they can improve your work.

Becoming A Chef

They say that the difference between a cook and a chef is that a cook follows a recipe, whereas a chef writes a recipe.

You’re becoming a chef for your impact model – dreaming, experimenting, documenting and improving your recipes as you learn.

Your job is to first think about what you really care about, what you are wanting to change, and what you want to see in the future.

Then you get to read other people’s recipes, as well as drafting your own.

You get to describe what sort of inputs you want to use and what activities you want to do with them.

Then you can test out what outputs these create, and what outcomes stem from the work in the future.

You can run pilots, build prototypes, measure your work and tweak the formulas.

You can share your ideas with your peers and advisors, learning how to improve your work or modify the recipe to suit new contexts.

It’s helpful to show people what the finished product looks like, and offer some pro tips on how they can avoid a calamity when they try it for themselves.

Most importantly, we hope you find joy in the process, because we need more diligent chefs doing their best to make genuine change.